So I just came to an amazing insight on the nature of life, and other systems generally:

There’s a big difference between superficial unity (e.g., something looks like a single object), and functional unity (e.g., an atom behaves as a single object). We know of examples of arguably random systems like cellular automata that exhibit superficial unity (they literally contain triangle-shaped outputs or Sierpinksi Traingles). But that’s not the same thing as an atom, that generally interacts as a single unit, or a composite particle, that again, despite being a complex object, behaves as a single unitary whole in general when interacting with other systems. And the reason I think this is connected to life, is because at least some people claim the origin of life stems from random interactions –

This is deeply unsatisfying, and in my opinion, an incomplete explanation of what’s happening.

Think about the probability of randomly producing something as large and complex as a DNA molecule, that has deep unitary functions, that copies itself, consumes its environment, and ends up generating macroscopic systems, that are also functionally unitary –

This is a ridiculous idea. For intuition, generate random characters on a page, and try to run them in C++, or whatever language you like –

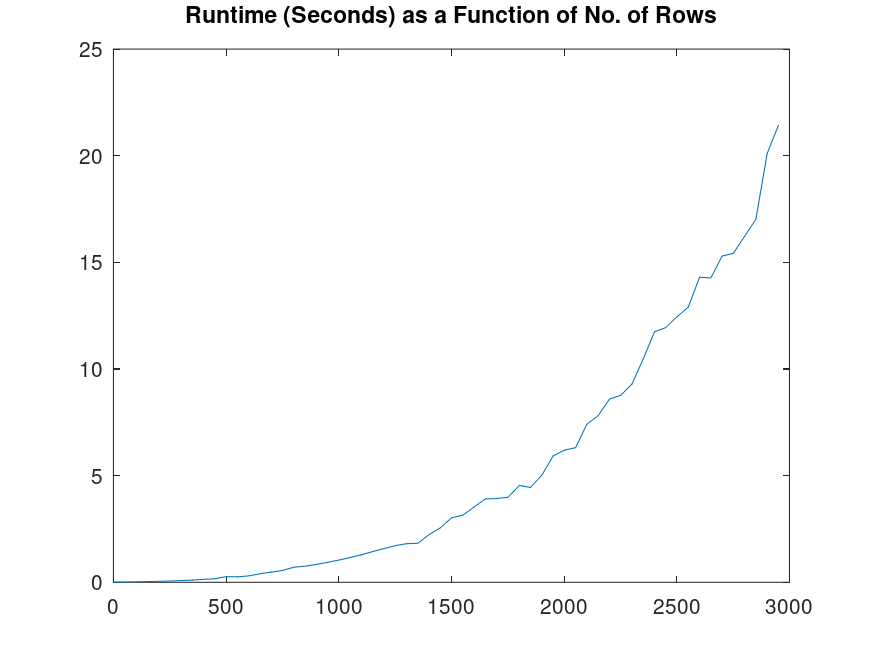

What’s the probability you’ll even produce a program that runs, let alone does something not only useful, but astonishing, and with an output that is orders of magnitude larger than the input program? There’s no amount of time that will make this idea make sense, and you’ll probably end up needing periods of time that exceed the age of the Universe itself. A simple for loop contains about 20 characters, and there are about 50 characters in scope in programming languages –

This is not realistic thinking, as a program of any real utility, will quickly vanish into the truly impossible, with even a simple given for loop having a probability that is around  . For context, there have been about

. For context, there have been about  seconds since the Big Bang. Let’s assume someone had a computer running at the time of the Big Bang, that could generate 1 billion possible programs per second. Every program generated is either a success or a failure, and let’s assume the probability of success is again

seconds since the Big Bang. Let’s assume someone had a computer running at the time of the Big Bang, that could generate 1 billion possible programs per second. Every program generated is either a success or a failure, and let’s assume the probability of success is again  . The binomial distribution in this case reduces to,

. The binomial distribution in this case reduces to,

where  is the number of trials and

is the number of trials and  is the probability of generating code that runs. Because we’ve assumed that our machine, that’s been around since inception, can test one billion possibilities per second, we would have a total number of trials given by

is the probability of generating code that runs. Because we’ve assumed that our machine, that’s been around since inception, can test one billion possibilities per second, we would have a total number of trials given by  . This yields a comically low probability that is

. This yields a comically low probability that is  , even given the absurd assumption, that calculations have been running since the Big Bang.

, even given the absurd assumption, that calculations have been running since the Big Bang.

Expressed in these terms, the idea that life is the product of chance, sounds absurd, and it is, but this doesn’t require direct creationism, though I think philosophers and scientists are still stuck with the fact that the Universe is plainly structured, which is strange. Instead, I think that we can turn to the atom, and composite particles, for an intuition as to how a molecule as complex as DNA could come into being. Specifically, I think that high energy, high complexity interactions cause responses from Nature, that impose simplicity, and literally new physics:

The physics inside an atom, is not the same as the physics outside an atom;

The physics inside a composite particle, is not the same as the physics outside a composite particle.

This does not preclude a unified theory, but instead perhaps e.g., different subsets or instances of the same general rules apply under different conditions, and that the rules change as a function of energy and complexity. So if e.g., you have a high-energy event, that is high in complexity, at the scale of the atom, then perhaps, this could give rise to a system like DNA. This is however, distinct from random processes that produce superficial or apparent unity (i.e., it looks like a shape), and is instead a process of Nature that imposes functional unity on systems that are sufficiently high in energy and complexity.

I am in some sense calling into question at least some of the work of people like Stephen Wolfram, that from what I remember, argue that the behavior of automata can be used to describe the behavior of living systems. I think instead you can correctly claim that automata produce patterns that are superficially similar to e.g., the coloring and shapes you find in Nature, but that’s not the same as producing a dynamic and unitary system, that superficially has a resemblance to the patterns you find in that area of computer science generally. The idea being that you have a discrete change from a complex churning physical system, into a single ordered system that behaves as a whole, and has its own physics that are again, distinct from the physics prior to this discrete change. It’s the difference producing a static artifact, that again has elements that are similar to known objects, and producing a dynamic artifact with those same superficial qualities. What’s interesting, is that we know heavy elements are produced in stars, which are plainly very high energy, very complex systems. Now think about how much larger and complex DNA is compared to even a large atom. If this theory is correct, then we would be looking for systems that aren’t necessarily as large as stars, but perhaps have even greater energy densities and complexities –

That’s quite the conundrum, because I don’t think such things occur routinely if at all on Earth. I think the admittedly possibly spurious logic suggests that higher energy stars, specifically black holes, might be capable of producing larger artifacts like large molecules. The common misconception that nothing escapes a black hole is simply incorrect, and not because of Hawking’s work, but because black holes are believed to have a lifespan, just like stars. As a result, any objects they create, could be released –

The intuition would be, powerful stars produce heavy elements, so even more powerful stars, like black holes, could produce molecules. And because the physics of black holes is plainly high energy and complex, it’s a decent candidate.

However, even if all of this is true, and we are able to someday replicate the conditions that give rise to life, we are still stuck with the alarming realization that there are apparently inviolate rules of the Universe, beyond physics, the causes of which are arguably inaccessible to us. Specifically, the theorems of combinatorics are absolute, and more primary than physics, since they are not subject to change or refinement –

They are absolute, inviolate rules of the Universe, and as a result, they don’t appear to have causes in time, like the Big Bang. They instead follow logically, almost outside time, from assumption. How did this come to be? And does that question even mean anything, for rules that seem to have no ultimate temporal cause? For these reasons, I don’t think there’s a question for science there, because it’s beyond cause. This is where I think the role of philosophy and religion truly comes into play, because there is, as far as I can tell, no access to causes beyond the mere facts of mathematics. That is, we know a given theorem is true, because there is a proof from a set of assumptions that are again totally inviolate –

Counting will never be incorrect, and neither will the laws of logic. And so we are instead left with an inquiry into why counting is correct, and why logic is correct, and I don’t think that’s subject to scientific inquiry. It simply is the case, beyond empiricism, though you could argue we trust the process because it’s always been observed to be the case. But this is dishonest, because everyone knows, in a manner that at least I cannot articulate in words, that you don’t need repeated observation to know that counting is inviolate. Moreover, I don’t think this is limited to combinatorics, but instead, would include any theorems that follow from apparently inviolate assumptions about the Universe. For example, the results I presented in “Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty” fit into this category, because they follow from a tautology that simply cannot be avoided. Further, the results I present in Section 1.4 of “A Computational Model of Time-Dilation” also fit this description, because all measurements of time, made by human beings, will be discrete, and so the results again follow from apparently inviolate assumptions about the Universe. And so we are stuck with the alarming realization that there are apparently inviolate rules of the Universe, the causes of which are arguably inaccessible to us. That is, the laws of combinatorics seem to be perennially true, that follow from idea itself, independent of any substance, and without succession from cause in time.

So in this view, even if the conditions of the origins of life are someday replicable, the real mystery is the context that causes life to spring into existence –

The causes of the laws of the Universe, being inaccessible, perhaps in contrast to the conditions that produce life.

To take this literally, the laws of combinatorics, actually exist, outside time and space, and yet impose conditions upon time and space, that are absolute and inviolate. This space, assuming it exists, would have a relational structure that is also absolute and inviolate, as the logical relationships among the theorems of combinatorics are also absolute and inviolate. It is in this view, only the peculiarity of our condition, that requires the progression through time, which allows for computation, and in turn, the discovery of these laws and relationships, whereas in reality, they simply exist, literally beyond our Universe, and are alluded to, by observation of our Universe. To return to the topic of life, without life, there would be no ideas, and instead, only the operations of their consequences (i.e., the undisturbed laws of physics). Because life exists, there is, in this view, a connection, between the space of ideas, and our Universe. To lend credence to this view, consider the fact that there are no constraints on the Universe, other than those imposed by some source. For example, the written laws of mankind, the limitations of the human body, the observed laws of physics, and ultimately, the theorems of combinatorics, which will never change. The argument above suggests that, therefore, the theorems of combinatorics have a source that is exogenous to both time and space, yet to deny a source to the most primordial and absolute restrictions of our Universe, seems awkward at best. Moreover, humanity’s progression through science has repeatedly struggled with that which is not directly observable by the human body, such as radio waves, magnetic fields, and gravity, yet we know something must be there. In this case, logic implies that the laws of combinatorics exist in a space, that by definition, must be beyond both time and space, though its consequences are obvious, and with us constantly, and so that space, must have dominion over time and space, and is, from our condition, absolute and inviolate.

I suppose if you consider, and if you believe, that the laws of mathematics themselves are the result of work, of design, then there is only a finite amount of work to do that follows, in light of what must be, a literally infinite amount of work to set the conditions that allow for life itself.