Friday evening I went on a tirade on Twitter about an idea I had for a robot a while back, but the core point has nothing to do with robotics itself, and is really about imitation. Specifically, what I said was, let’s imagine you have a machine that has a set of physical controls capable of executing incremental physical change. For example, the signal causes a piston to lift some marginal distance. There is therefore in every case a set of signals

, and their resultant motions. Let’s assume the machine in question can compare its own current state to the state of some external system it’s trying to imitate, which could of course be a dataset. Returning to the previous example, imagine a machine trying to imitate a pumping motion –

It would then compare the motions of the piston to the motions in the dataset that describe that desired motion in question, and this will produce some measure of distance.

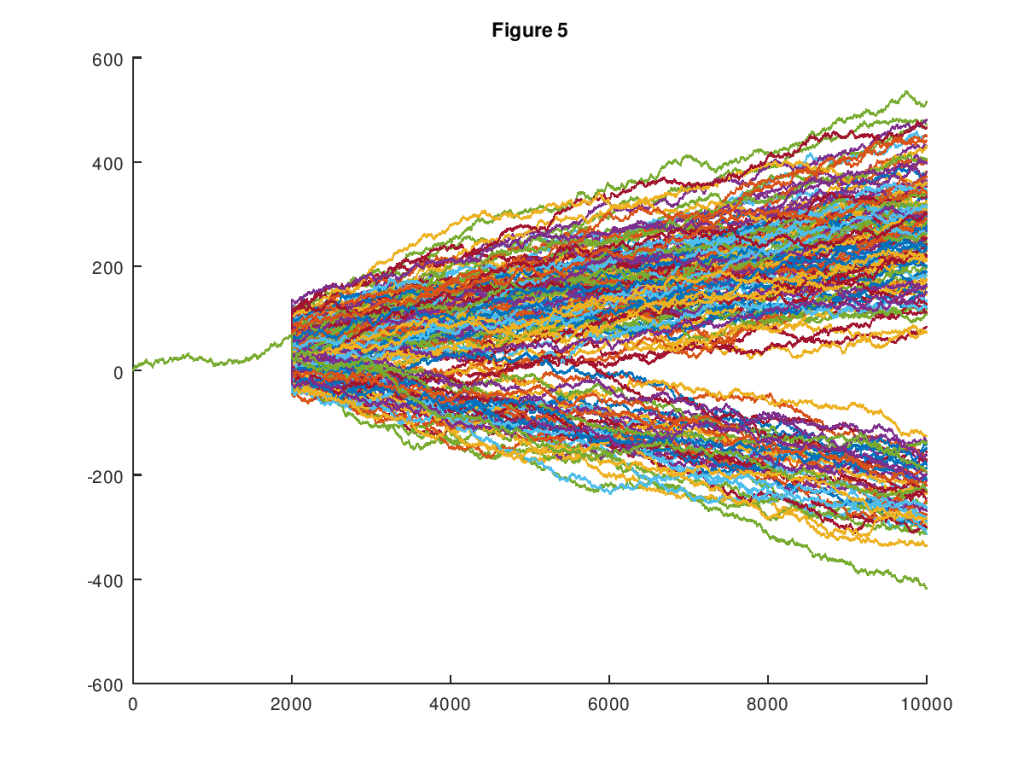

Now imagine a control system that fires the appropriates motions in order when given the vector . If there are

possible signals, and therefore

possible motions, then we can use a Monte Carlo simulator to generate a large number of vectors, in parallel, and therefore, a large number of motions. The machine can then test the incremental change that occurs as a result of executing the sequence encoded in each resultant

, and compare it to the motions it’s trying to imitate, again in parallel. Obviously, you select the motion that minimizes the difference between the desired motion and the actual motion, and if you need tie-breakers, you look to the standard deviation of velocities, or the entropies of the velocities, each of which should help achieve smoothness. This obviously requires the machine to have a model of its own state, but you could also imagine a factory floor filled with the same machines, all learning from each other –

This happens anyway, so why not utilize the fact that you have a bunch of the same machines in the same place, to allow them to actually test motions, physically, in parallel. This would be the case where outcome is measured, rather than modeled. This could prove quite powerful, because you don’t need a machine to calculate what’s going to happen, but instead, the machine can rely upon observation, piggybacking off of the computational power of Nature itself. If what’s going to happen is complex, and therefore computationally intensive, this could prove extremely useful, because you can achieve true parallelization through manufacturing that’s going to happen anyway, if you’re producing at scale. I had this idea a while back, regarding engines, but the more general idea seems potentially quite powerful.

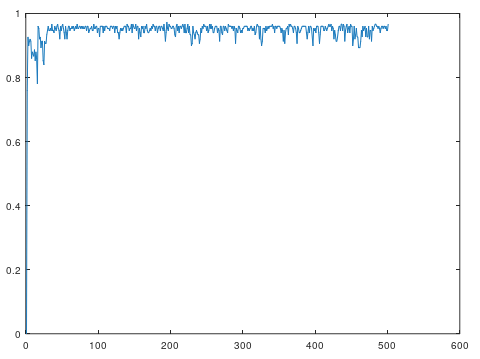

We can apply the same kind of optimizer I used in classifications in this process, which should allow us to navigate the state space of motions efficiently.