Redux And Reduction

In the previous article, we defined a highly abstract framework that considered the subjective expected payout of both sides of a fixed fee derivative. In this article, we will apply that model to the context of credit default swaps and will show that the presence of credit default swaps and synthetic bonds should be expected to reduce the demand for “real” bonds (as opposed to synthetic bonds) and thereby reduce the net exposure of an economy to credit risk.

The Demand For Credit Default Swaps

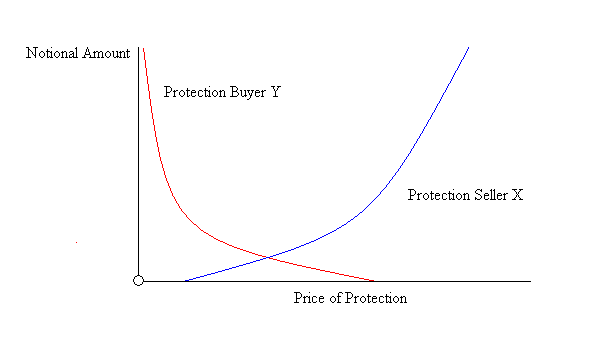

In the previous article, we plotted the expected payout of each party to a credit default swap as a function of the fee and each party’s subjective valuation of the probability that a default will occur. The simple observation gleaned from that chart was that if we fix the subjective probabilities of default, protection sellers expect to earn more as the price of protection increases and protection buyers expect to earn more as the price of protection decreases. Thus, as the the price of protection increases, we would expect protection seller side “demand” to increase and expect protection buyer side “demand” to decrease. But how can demand be expressed in the context of a credit derivative? The general idea is to assume that holding all other variables constant, the size of the desired notional amount of the CDS will vary with price. So in the case of protection sellers, the greater the price of protection, the greater the notional amount desired by any protection seller.

In order to further formalize this concept, we should consider each reference entity as defining a unique demand curve for each market participant. We should also distinguish between demand for buying protection and demand for selling protection. For convenience’s sake, we will refer to the demand for selling protection as the supply of credit protection and demand for buying credit protection as the demand for credit protection. For example, consider protection seller X’s supply curve and protection buyer Y’s demand curve for CDSs naming ABC as a reference entity. The following chart expresses the total notional amount of all CDSs desired by X and Y as a function of the price of protection.

As the price of protection approaches zero, Y’s desired notional amount should approach infinity, since at zero, Y is getting free protection and should desire an unbounded “quantity” of credit protection. The same is true for X as the price of protection approaches infinity.

Synthetic Bonds As Competing Goods With “Real” Bonds

Imagine a world without credit derivatives and therefore without synthetic bonds. In that world, there will be a demand curve for real ABC bonds as a function of the spread the bonds pay over the risk free rate, holding all over variables constant. Now imagine that credit default swaps were introduced to this world. We know that the cash flows of any bond can be synthesized using Treasuries and credit default swaps. For example, assume we have synthesized the cash flows of ABC’s bonds using the method described here. We would expect at least some investors to be indifferent between real ABC bonds and synthetic ABC bonds, since they both produce the same cash flows. Thus, the two are competing products in the sense that investors in real ABC bonds should be potential investors in synthetic ABC bonds. So because some investors will be indifferent between synthetic ABC bonds and real ABC bonds, synthetic ABC bonds will siphon some of the cash that would have otherwise gone to real ABC bonds. Thus, in a world with credit derivatives, we would expect there to be less demand for real bonds than would be present without credit derivatives. In the following chart we express the macroeconomic demand for real ABC bonds in terms of the spread over the risk free rate and the total par value desired by the market.

Thus, the demand for credit derivatives diminishes the demand for real bonds. Although we cannot know exactly what the effect on the demand curve for real bonds will be, we can safely assume that it will be diminished at all levels of return, since at each level, at least some investors will be indifferent to real bonds and synthetic bonds, since each offers the same return.

Real Cash Losses Versus Wealth Transfers Through Derivatives

Economics already has a term to describe payouts under credit default swaps: wealth transfers. Although ordinarily used to describe the cash flows of tax regimes, the term applies equally to the payments under a credit default swap. As described in the previous article, there are no net cash losses under a credit default swap. There is a payment of money from one party to another, the net effect of which is a wealth transfer. That is, credit default swaps, like all derivatives, simply rearrange the current allocation of cash in the financial system, and nothing is lost in process (ignoring transaction costs, which are not relevant to this discussion).

When a real bond defaults, a net cash loss occurs. The borrower has taken the money lent to it by investors, lost it, and the investors are not fully paid back. Therefore, both the borrower and the investors incur a cash loss, creating a net cash loss to the economy. So, in the case of a synthetic ABC bond, upon the default of one of ABC’s bonds, a wealth transfer occurs from the protection seller to the protection buyer and the net effect is null. In the case of a real ABC bond, upon the default of that bond, the investors will lose some of their principle and ABC has already lost some of the money it was lent, the net effect of which is a loss to the economy.

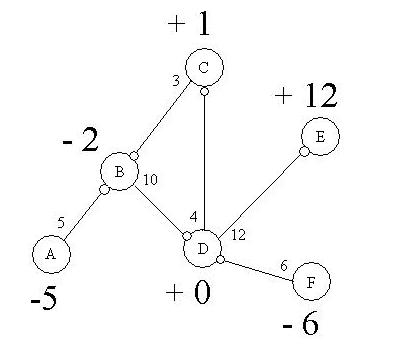

So every dollar siphoned away from real bonds by synthetic bonds is a dollar that will not be lost in the economy upon the occurrence of a credit event. If there were no credit derivatives, then that dollar would have been invested in real bonds and thereby lost upon the occurrence of a credit event. Therefore, the net losses to the economy upon the occurrence of a credit event is less with credit derivatives than without. In the following diagram, the two circles of each transaction represent the parties to that transaction. In the case of real bonds, one of the parties is ABC and the other is an investor. In the case of synthetic bonds, one is the protection seller and the other is the protection buyer of the credit default swap underlying the synthetic bond.

This diagram simply demonstrates what was described above. Namely, that with credit derivatives, some investors will choose synthetic bonds rather than real bonds, thereby reducing the amount of cash exposed to credit risk. Thus, rather than increase the impact of credit risk, credit default swaps actually decrease the impact of credit risk by placating the demand for exposure to credit risk with synthetic instruments that are incapable of producing net losses. However, there may be consequences arising from credit default swaps that cause actual cash losses to an economy, such as a firm failing because of its obligations under credit default swaps. But the failure is not caused by the instrument itself. The nature of the instrument is to reduce the impact of credit risk. The firm’s failure is caused by that firm’s own poor risk management.