A Higher Plane

In this article, I will return to the ideas proposed in my article entitled, “A Conceptual Framework For Analyzing Systemic Risk,” and once again take a macro view of the role that derivatives play in the financial system and the broader economy. In that article, I said the following:

“Practically speaking, there is a limit to the amount of risk that can be created using derivatives. This limit exists for a very simple reason: the contracts are voluntary, and so if no one is willing to be exposed to a particular risk, it will not be created and assigned through a derivative. Like most market participants, derivatives traders are not in engaged in an altruistic endeavor. As a result, we should not expect them to engage in activities that they don’t expect to be profitable. Therefore, we can be reasonably certain that the derivatives market will create only as much risk as its participants expect to be profitable.”

The idea implicit in the above paragraph is that there is a level of demand for exposure to risk. By further formalizing this concept, I will show that if we treat exposure to risk as a good, subject to the observed law of supply and demand, then credit default swaps should not create any more exposure to risk in an economy than would be present otherwise and that credit default swaps should be expected to reduce the net amount of exposure to risk. This first article is devoted to formalizing the concept of the price for exposure to risk and the expected payout of a derivative as a function of that price.

Derivatives And Symmetrical Exposure To Risk

As stated here, my own view is that risk is a concept that has two components: (i) the occurrence of an event and (ii) a magnitude associated with that event. This allows us to ask two questions: What is the probability of the event occurring? And if it occurs, what is the expected value of its associated magnitude? We say that P is exposed to a given risk if P expects to incur a gain/loss if the risk-event occurs. We say that P has positive exposure if P expects to incur a gain if the risk-event occurs; and that P has negative exposure if P expects to incur a loss if the risk-event occurs.

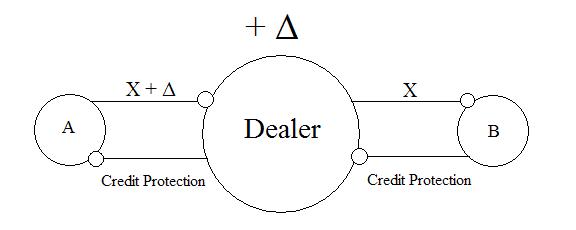

Exposure to any risk assigned through a derivative contract will create positive exposure to that risk for one party and negative exposure for the other. Moreover the magnitudes of each party’s exposure will be equal in absolute value. This is a consequence of the fact that derivatives contracts cause payments to be made by one party to the other upon the occurrence of predefined events. Thus, if one party gains X, the other loses X. And so exposure under the derivative is perfectly symmetrical. Note that this is true even if a counterparty fails to pay as promised. This is because there is no initial principle “investment” in a derivative. So if one party defaults on a payment under a derivative, there is no cash “loss” to the non-defaulting party. That said, there could be substantial reliance losses. For example, you expect to receive a $100 million credit default swap payment from XYZ, and as a result, you go out and buy $1,000 alligator skin boots, only to find that XYZ is bankrupt and unable to pay as promised. So, while there would be no cash loss, you could have relied on the payments and planned around them, causing you to incur obligations you can no longer afford. Additionally, you could have reported the income in an accounting statement, and when the cash fails to appear, you would be forced to “write-down” the amount and take a paper loss. However, the derivatives market is full of very bright people who have already considered counterparty risk, and the matter is dealt with through the dynamic posting of collateral over the life of the agreement, which limits each party’s ability to simply cut and run. As a result, we will consider only cash losses and gains for the remainder of this article.

The Price Of Exposure To Risk

Although parties to a derivative contract do not “buy” anything in the traditional sense of exchanging cash for goods or services, they are expressing a desire to be exposed to certain risks. Since the exposure of each party to a derivative is equal in magnitude but opposite in sign, one party is expressing a desire for exposure to the occurrence of an event while the other is expressing a desire for exposure to the non-occurrence of that event. There will be a price for exposure. That is, in order to convince someone to pay you $1 upon the occurrence of event E, that other person will ask for some percentage of $1, which we will call the fee. Note that as expressed, the fee is fixed. So we are considering only those derivatives for which the contingent payout amounts are fixed at the outset of the transaction. For example, a credit default swap that calls for physical delivery fits into this category. As this fee increases, the payout shrinks for the party with positive exposure to the event. For example, if the fee is $1 for every dollar of positive exposure, then even if the event occurs, the party with positive exposure’s payments will net to zero.

This method of analysis makes it difficult to think in terms of a fee for positive exposure to the event not occurring (the other side of the trade). We reconcile this by assuming that only one payment is made under every contract, upon termination. For example, assume that A is positively exposed to E occurring and that B is negatively exposed to E occurring. Upon termination, either E occurred prior to termination or it did not.

If E did occur, then B would pay to A, where F is the fee and N is the total amount of A’s exposure, which in the case of a swap would be the notional amount of the contract. If E did not occur, then A would pay

. If E is the event “ABC defaults on its bonds,” then A and B have entered into a credit default swap where A is short on ABC bonds and B is long. Thus, we can think in terms of a unified price for both sides of the trade and consider how the expected payout for each side of the trade changes as that price changes.

Expected Payout As A Function Of Price

As mentioned above, the contingent payouts to the parties are a function of the fee. This fee is in turn a function of each party’s subjective valuation of the probability that E will actually occur. For example, if A thinks that E will occur with a probability of , then A will accept any fee less than .5 since A’s subjective expected payout under that assumption is

. If B thinks that E will occur with a probability of

, then B will accept any fee greater than .25 since his expected payout is

. Thus, A and B have a bargaining range between .25 and .5. And because each perceives the trade to have a positive payout upon termination within that bargaining range, they will transact. Unfortunately for one of them, only one of them is correct. After many such transactions occur, market participants might choose to report the fees at which they transact. This allows C and D to reference the fee at which the A-B transaction occurred. This process repeats itself and eventually market prices will develop.

Assume that A and B think the probability of E occurring is and

respectively. If A has positive exposure and B has negative, then in general the subjective expected payouts for A and B are

and

respectively. If we plot the expected payout as a function of F, we get the following:

The red line indicates the bargaining range. Thus, we can describe each participant’s expected payout in terms of the fee charged for exposure. This will allow us to compare the returns on fixed fee derivatives to other financial assets, and ultimately plot a demand curve for fixed fee derivatives as a function of their price.