Genetic Alignment

Because of relatively recent advances in genetic sequencing, we can now read entire mtDNA genomes. However, because mtDNA is circular, it’s not clear where you should start reading the genome. As a consequence, when comparing two genomes, you have no common starting point, and the selection of that starting point will impact the number of matching bases. As a simple example, consider the two fictitious genomes and

. If we count matching bases using the first index of each genome, then the number of matching bases is zero. If instead we start at the first index of

and the second index of

(and loop back around to the first ‘G’ of

), the match count will be four, or 100% of the bases. As such, determining the starting indexes for comparison (i.e., the genome alignment) is determinative of the match count.

It turns out that mtDNA is unique in that it is inherited directly from the mother, generally without any mutations at all. As such, the intuition for combinations of sequences typically associated with genetics is inapplicable to mtDNA, since there is no combination of traits or sequences inherited from the mother and the father, and instead a basically perfect copy of the mother’s genome is inherited. As a result, it makes perfect sense to use a global alignment, which we did above, where we compared one entire genome to another entire genome

. In contrast, we could instead make use of a local alignment, where we compare segments of two genomes.

For example, consider genomes and

. First you’ll note these genomes are not the same length, unlike in the example above, which is another factor to be considered when developing an alignment for comparison. If we simply use the first three bases of each genome for comparison, then the match count will be one, since the first two initial ‘A’s match. If instead we use index two of

and index one of

, then the entire

sequence matches, and the resultant match count will be three.

Note that the number of possible global alignments is simply the length of the genome. That is, when using a global alignment, you “fix” one genome, and “rotate” the other, one base at a time, and that will cover all possible global alignments between the two genomes. In contrast, the number of local alignments is much larger, since you have to consider all local alignments of each possible length. As a result, it is much easier to consider all possible global alignments between two genomes, than local alignments. In fact, it turns out there is exactly one plausible global alignment for mtDNA, making global alignments extremely attractive in terms of efficiency. Specifically, it takes 0.02 seconds to compare a given genome to my entire dataset of roughly 650 genomes using a global alignment. Performing the same task using a local alignment takes one hour, and the algorithm I’ve been using considers only a small subset of all possible local alignments. That said, local alignments allow you to take a closer look at two genomes, and find common segments, which could indicate a common evolutionary history. This note discusses global alignments, I’ll write something soon that discusses local alignments, as a second look to support my work on mtDNA generally.

Nearest Neighbor

The Nearest Neighbor algorithm can provably generate perfect accuracy for certain Euclidean datasets. That said, DNA is obviously not Euclidean, and as such, the results I proved do not hold for DNA datasets. However, common sense suggests we might as well try it, and it turns out, you get really good results that are significantly better than chance. To apply the Nearest Neighbor algorithm to an mtDNA genome , we simply find the genome

that has the most bases in common with

, i.e., its best match in the dataset, and hence, its “Nearest Neighbor”. Symbolically, you could write

. As for accuracy, using Nearest Neighbor to predict the ethnicity of each individual in my dataset produces an accuracy of 30.87%, and because there are 75 global ethnicities, chance implies an accuracy of

. As such, we can conclude that the Nearest Neighbor algorithm is not producing random results, and more generally, produces results that provide meaningful information about the ethnicities of individuals based solely upon their mtDNA, which is remarkable, since ethnicity is a complex trait, that clearly should depend upon paternal ancestry as well.

The Global Distribution of mtDNA

It turns out the distribution of mtDNA is truly global, and a result, we should not be surprised that the accuracy of the Nearest Neighbor method as applied to my dataset is a little low, though as noted, it is significantly higher than chance and therefore plainly not producing random predictions. That is, if we ask what is e.g., the best match for a Norwegian genome, you could find that it is a Mexican genome, which is in fact the case for this Norwegian genome. Now you might say this is just a Mexican person that lives in Norway, but I’ve of course thought of this, and each genome has been diligenced to ensure that the stated ethnicity of the person is e.g., Norwegian.

Now keep in mind that this is literally the closest match for this Norwegian genome, and it’s somehow on the other side of the world. But high school history teaches us about migration over the Bering Strait, and this could literally be an instance of that, but it doesn’t have to be. The bottom line is, mtDNA mutates so slowly, that outcomes like this are not uncommon. In fact, by definition, because the accuracy of the Nearest Neighbor method is 38.07% when applied to predicting ethnicity, it must be the case that 100% – 38.07% = 69.13% of genomes have a Nearest Neighbor that is of a different ethnicity.

One interpretation is that, oh well, the Nearest Neighbor method isn’t very good at predicting ethnicity, but this is simply incorrect, because the resultant match counts are almost always over 99% of the entire genome. Specifically, 605 of the 664 genomes in the dataset (i.e., 91.11%) map to a Nearest Neighbor that is 99% or more identical to the genome in question. Further, 208 of the 664 genomes in the dataset (i.e., 31.33%) map to a Nearest Neighbor that is 99.9% or more identical to the genome in question. The plain conclusion is that more often than not, nearly identical genomes are found in different ethnicities, and in some cases, the distances are enormous.

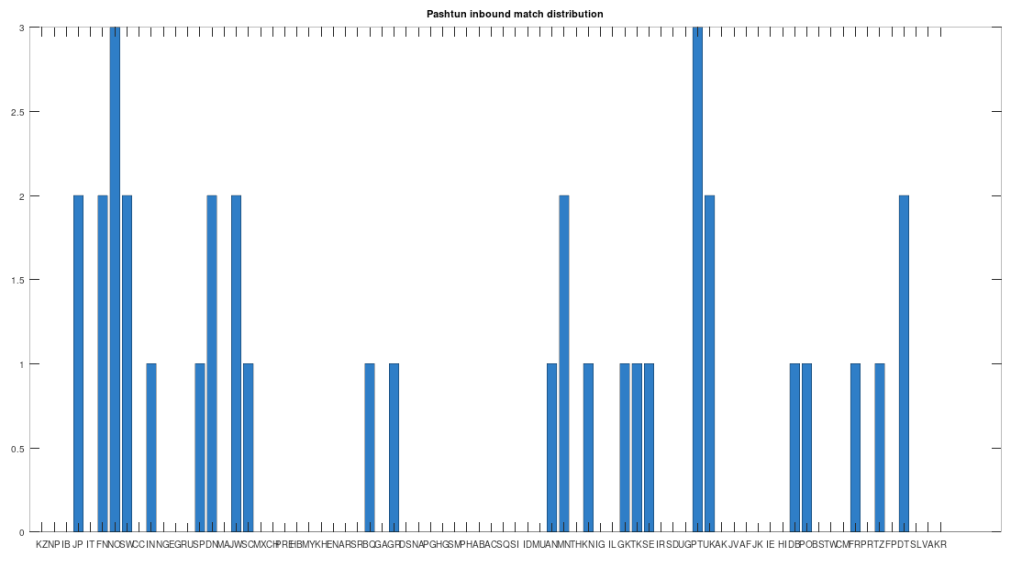

In particular, the Pashtuns are the Nearest Neighbors of a significant number of global genomes. Below is a chart showing the number of times (by ethnicity) that a Pashtun genome was a Nearest Neighbor of that ethnicity. So e.g., returning to Norway (column 7), there are 3 Norwegian genomes that have a Pashtun Nearest Neighbor, and so column 7 has a height of 3. More generally, the chart is produced by running the Nearest Neighbor algorithm on every genome in the dataset, and if a given genome maps to a Pashtun genome, we increment the applicable column for the genome’s ethnicity (e.g., Norway, column 7). There are 20 Norwegian genomes, so of Norwegian genomes map to Pashtuns, who are generally located in Central Asia, in particular Afghanistan. This seems far, but in the full context of human history, it’s really not, especially given known migrations, which covered nearly the whole planet.

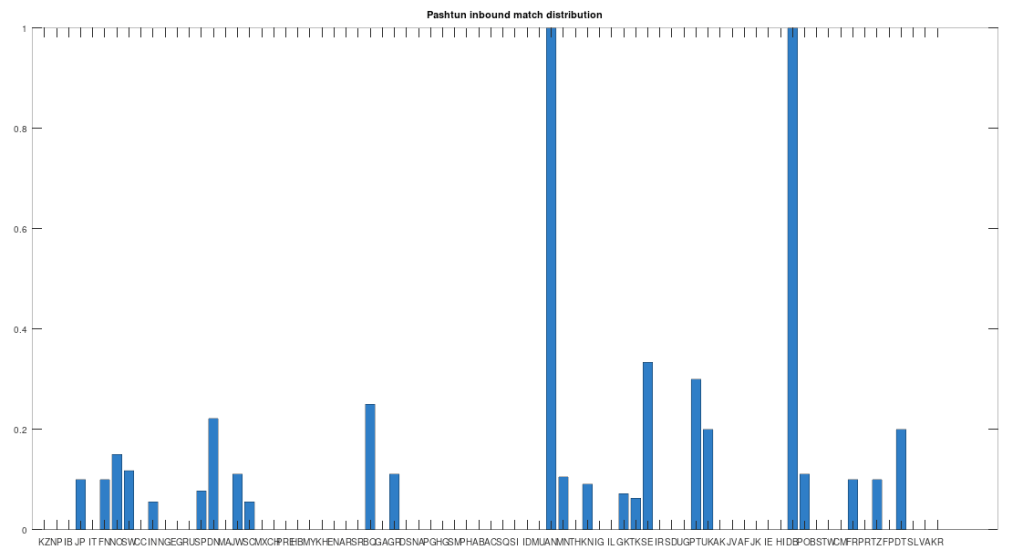

The chart above is not normalized to show percentages, and instead shows the integer number of Pashtun Nearest Neighbors for each column. However, it turns out that a significant percentage of genomes in ethnicities all over the world map to the Pashtuns, which is just not true generally of other ethnicities. That is, it seems the Pashtuns are a source population (or closely related to that source population) of a significant number of people globally. This is shown in the chart below, which is normalized by dividing each column by the number of genomes in that column’s population, producing a percentage.

As you can see, a significant percentage of Europeans (e.g., Finland, Norway, and Sweden, columns 6, 7, and 8 respectively), East Asians (e.g., Japan and Mongolia, columns 4 and 44, respectively), and Africans (e.g., Kenya and Tanzania, columns 46 and 70, respectively), have genomes that are closest to Pashtuns. Further, the average match count to a Pashtun genome over this chart is , so these are plainly meaningful, nearly identical matches. Finally, these Pashtun genomes that are turning up as Nearest Neighbors are heterogeneous. That is, it’s not the case that a single Pashtun genome is popping up globally, and instead, multiple distinct Pashtun genomes are popping up globally as Nearest Neighbors. One not-so-plausible explanation that I think should be addressed is the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, which overlaps quite a bit with the geography of the Pashtuns. The hypothesis would be that Ancient Greeks brought European mtDNA to the Pashtuns. Maybe, but I don’t think Alexander the Great made it to Japan, so we need a different hypothesis to explain the global distribution of Pashtun mtDNA.

All of this is instead consistent with what I’ve called the Migration-Back Hypothesis, which is that humanity begins in Africa, migrates to Asia, and then migrates back to Africa and Europe, and further into East Asia. This is a more general hypothesis that many populations, including the Pashtuns, migrated back from Asia to Africa and Europe, and extended their presence into East Asia. The question is, can we also establish that humanity began in Africa using these and other similar methods? Astonishingly, the answer is yes, and this is discussed at some length in a summary on mtDNA that I’ve written.