Insurable Interests

When you purchase fire insurance on your own home, you are said to have an insurable interest. That is, you have an interest in something and you’d like to insure it against a certain risk. In the case of fire insurance, the insurable interest is your house and the risk is fire burning your house down. Through an insurance policy, and in exchange for a fee, you can effectively transfer, to some 3rd party, financial exposure to the risk that your insurable interest (house) will burn down.

When you purchase protection on a bond through a credit default swap, you may or may not own the underlying bond. As such, you may or may not have something analogous to an insurable interest. David Merkel over at The Aleph Blog brought this issue to my attention in a comment on one of my many rants about credit default swaps. Although you should read his article in its entirety, his argument goes like this: just like you wouldn’t want someone you don’t know taking out a life insurance policy on you (because that would give them an incentive to contribute to your death), corporation ABC doesn’t want swap dealers selling protection on their bonds to those who don’t own them (since these buyers would profit from ABC’s failure). Technically, ABC wouldn’t want protection being sold to those that have a negative economic interest in ABC’s debt.

Courting Disaster

We might find it objectionable that one person takes out an insurance policy on the life of another. This is understandable. After all, we don’t want to incentivize murder. But we already incentivize creating illness. Doctors, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies all have incentives to create illnesses that only they can cure, thus diverting money from other economic endeavors their way. More importantly, even if you don’t accept the “it’s no big deal” argument, insurance contracts have a feature that prevents the creation of incentives to destroy life and property: they are voluntary, just like derivatives.

In order for you to purchase a policy on my life, someone has to sell it to you. And like most businesses, insurance businesses are not engaged in an altruistic endeavour. So, when you come knocking on their door asking them to issue a $100 million policy on my life, they will be suspicious, and rightfully so. They will probably realize that given the fact that you are not me, $100 million is probably enough money to provide you with an incentive to have me end up under a bus. And of course, they will not issue the policy. But not because they care whether or not I end up under a bus. Rather, they will not issue the policy because it’s a terrible business decision. They know that it doesn’t cost much to kill someone, and therefore, as a general idea, issuing life insurance policies to those who have no interest in the preservation of the insured life is a bad business decision. The same applies to policies on cars, houses, etc that the policy holder doesn’t own. As is evident, the concept of an insurable interest is simply a reflection of common sense business decisions.

You Sunk My Battleship

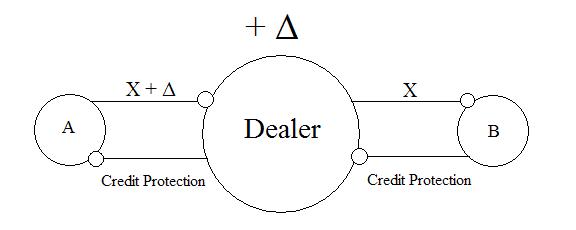

So why do swap dealers sell protection on ABC’s bonds to people that don’t own them? Isn’t that the same as selling a policy on my life to you? Aren’t they worried that the protection buyer will go out and destroy ABC? Clearly, they are not. If you read this blog often, you know that swap dealers net their exposure. So, is that why they’re not worried? No, it is not. Even though the swap dealer’s exposure is neutral, if the dealer sold protection to one party, the dealer bought protection from another. While the network of transactions can go on for a while, it must be the case that if one party is a net buyer of protection, another is a net seller. So, somewhere along the network, someone is exposed as a net buyer and another is exposed as a net seller.

So aren’t the net sellers worried that the net buyers will go out and destroy ABC? Clearly, they are not. The only practical way to gain the ability to run a company into the ground is to gain control of it. And the only practical way to gain control of it is to purchase a large stake in it. This is an enormous barrier. A would be financial assassin would have to purchase a large enough stake to gain control and at the same time purchase more than that amount in protection through credit default swaps, and do so without raising any eyebrows. If this sounds ridiculous it’s because it is. But even if you think it’s a viable strategy, ABC should be well aware that there are those in the world who would benefit from the destruction of their company. This is not unique to protection buyers, but applies also to competitors who would love to take ABC over and liquidate their assets and take over their distribution network; or plain vanilla short sellers; or environmentalist billionaires who despise ABC’s tire burning business. In short, ABC should realize that there are those who are out to get them, whatever their motive or method, and plan accordingly.

Hands Off My Ether

The fact that others are willing to sell protection on ABC to those who don’t own ABC bonds suggests that any insurable interest that ABC has is economically meaningless. For if it weren’t the case, as in the life policy examples, no one would sell protection. But they do. So, it follows that protection sellers don’t buy the arguments about the opportunities for murderous arbitrage. So what is ABC left with? An ethereal and economically meaningless right to stop other people from referencing them in private contracts. This is akin to saying “you can’t talk about me.” That is, they are left with the right to stop others from trespassing on their credit event. And that’s just strange.