Systemic Speculation

Pundits from all corners have been chiming in on the debate over derivatives. And much like the discourse that has dominated the rest of human history, reason, temperance, and facts play no role in the debate. Rather, the spectacular, outrage, and irrational blame have been the big winners lately. As a consequence, credit default swaps have been singled out as particularly dangerous to the financial system. Why credit default swaps have been targeted as opposed to other derivatives is not entirely clear to me, although I do have some theories. In this article I debunk many of the common myths about credit default swaps that are circulating in the popular press. For an explanation of how credit default swaps work, see this article.

The CDS Market Is Not The Largest Thing Known To Humanity

The media likes to focus on the size of the market, reporting shocking figures like $45 trillion and $62 trillion. These figures refer to the notional amount of the contracts, and because of netting, these figures do not provide a meaningful picture of the amount of money that will actually change hands. That is, without knowing the structure of the credit default swap market, we cannot determine the economic significance of these figures. As such, these figures should not be compared to real economic indicators such as GDP.

But even if you’re too lazy to think about how netting actually operates, why would you focus on credit default swaps? Even assuming that the media’s shocking double digit trillion dollar amounts have real economic significance, the credit default swap market is not even close in scale to the interest rate swap market, which is an even more shocking $393 trillion market. But alas, we are in the midst of a “credit crisis” and not an “interest rate crisis.” As such, headlines containing the terms “interest rate swap” will not fare as well as those containing “credit default swap” in search engines or newsstands. Perhaps one day interest rate swaps will have their moment in the sun, but for now they are an even larger and equally unregulated market that’s just as boring and uneventful as the credit default swap market.

Credit Default Swaps Do Not Facilitate “Gambling”

One of the most widely stated criticisms of credit default swaps is that they are a form of gambling. Of course, this allegation is made without any attempt to define the term “gambling.” So let’s begin by defining the term “gambling.” In my mind, the purest form of gambling involves the wager of money on the outcome of events that cannot be controlled or predicted by the person making the wager. For example, I could go to a casino and place a $50 bet that if a casino employee spins a roulette wheel and spins a ball onto the wheel, the ball will stop on the number 3. In doing so, I have posted collateral that will be lost if an event (the ball stopping on the number 3) fails to occur, but will receive a multiple of my collateral if that event does indeed occur. I have no ability to affect the outcome of the event and more importantly for our purposes, I have absolutely no way of predicting what the outcome will be. In short, my “investment” is a blind guess as to the outcome of a random event.

Now let’s compare that with someone (B) buying protection on ABC’s bonds through a credit default swap. Assume that B is as villainous as he could be: that is, assume that he doesn’t own the underlying bond. This evildoer is in effect betting upon the failure of ABC. What a nasty thing to do. And why would he do such a thing? Well, B might reasonably believe that ABC is going to fail in the near future based on market conditions and information disclosed by ABC. But why should someone profit from ABC’s failure? Because if B’s belief in ABC’s impending failure is shared by others, their collective selfish desire to profit will push the price of protection on ABC’s bonds up, which will signal to the market-at-large that the CDS market believes that there will be an event of default on ABC issued debt. That is, a market full of people who specialize in recognizing financial disasters will inadvertently share their expertise with the world.

So, in the case of the roulette wheel, we have money committed to the occurrence of an event that cannot be controlled or predicted by the person making the commitment. Moreover, this “investment” is made for no bona fide economic purpose with an expected negative return on investment. In the case of B buying protection through a CDS on a bond he did not own, we have money committed to the occurrence of an event that cannot be controlled by B but can be reasonably predicted by B, and through collective action we have the serendipitous effect of sharing information. To call the latter gambling is to call all of investing gambling. For there is no difference between the latter and buying stock, buying bonds, investing in the college education of your children, etc.

The Credit Default Swap Market Is Not An Insurance Market

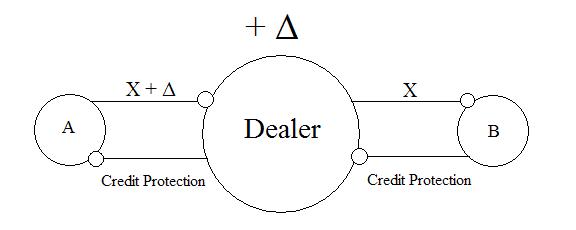

Credit default swaps operate like insurance at a bilateral level. That is, if you only focus on the two parties to a credit default swap, the agreement operates like insurance for both parties. But to do so is to fail to appreciate that a credit default swap is exactly that: a swap, and not insurance. Swap dealers are large players in the swap markets that buy from one party and sell to another, and pocket the difference between the prices at which they buy and sell. In the case of a CDS dealer, dealer (D) sells protection to A and then buys protection from B, and pockets the difference in the spreads between the two transactions. If either A or B has dodgy credit, D will require collateral. Thus, D’s net exposure to the bond is neutral. While this is a simplified explanation, and in reality D’s neutrality will probably be accomplished through a much more complicated set of trades, the end goal of any swap dealer is to get close to neutral and pocket the spread.

That said, insurance companies such as MBIA and AIG did participate in the CDS market, but they did not follow the business model of a swap dealer. Instead, they applied the traditional insurance business model to the credit default swap market, with notoriously less than stellar results. The traditional insurance business model goes like this: issue policies, estimate liabilities on those policies using historical data, pool enough capital to cover those estimated liabilities, and hopefully profit from the returns on the capital pool and the fees charged under the policies. Thus, a traditional insurer is long on the assets it insures while a swap dealer is risk-neutral to the assets on which it is selling protection, so long as its counterparties pay. So, a swap dealer is more concerned about counterparty risk: the risk that one of its counterparties will fail to payout. As mentioned above, if either counterparty appears as if it is unable to pay, it will be required to post collateral. Additionally, as the quality of the assets on which protection is written deteriorates, more collateral will be required. Thus, even in the case of counterparty failure, collateral will mitigate losses.

This collateral feature is missing on both ends of the traditional insurance model. Better put, there is no “other end” for a traditional insurer. That is, the insurance business model does not hedge risk, it absorbs it. So if a traditional insurer sold protection on bonds that had risks it didn’t understand, e.g., mortgage backed securities, and it consequently underestimated the amount of capital it needed to store to meet liabilities, it would be in some serious trouble. A swap dealer in the same situation, even if its counterparties failed to appreciate these same risks, would be compensated gradually over the life of the agreement through collateral.