Also published on the Atlantic Monthly’s Business Channel.

Joe Nocera has said his peace with respect to Obama’s proposed overhaul of the financial system. And in doing so, he expressed disappointment with several aspects of the proposal. In particular, he is displeased that the proposal “doesn’t attempt to diminish the use of … bespoke derivatives.” That certainly sounds ominous. But it’s also not true.

The proposal calls for increased capital charges on bespoke trades, which is a strong incentive away from them. But frankly, I’m sick of writing about the proposal. So rather than regurgitate and parse the administration’s plans for financial regulation, I’d like to take a moment to get familiar with some of the key concepts at play in the proposal, so that you can read it and come to your own conclusions. The two core areas I focus on here are derivatives and regulatory capital. With an understanding of these two areas, you should be able to get a grasp on what the administration is thinking and what effects the proposal will have in practice.

OTC Derivatives

I write about OTC derivatives pretty often, so rather than reinvent the wheel, I’ll shamelessly reuse a piece of introductory text I have handy:

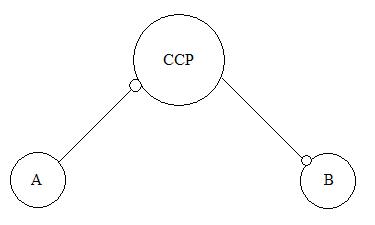

A derivative is a contract that derives its value by reference to “something else.” That something else can be pretty much anything that can be objectively observed and measured. That said, when people talk about derivatives, the “something else” is usually an index, rate, or security. For example, an option to purchase common stock is a fairly well-known and ubiquitous derivative. So are futures for commodities such as pork belly and oil. However, these are not the kind of derivatives that [the proposal] is talking about. [The proposal] is talking about OTC derivatives, or “over the counter” derivatives. This category of derivatives includes the much maligned “credit default swap” market, as well as other larger but apparently less notorious markets, such as the interest rate and foreign exchange derivatives markets. The key defining characteristic of an OTC derivative is that it is entered into directly between the parties. This is in contrast to exchange-traded derivatives, such as options to purchase common stock. Highly bespoke OTC derivatives are often negotiated at length between the parties and involve a great deal of collaboration between bankers, lawyers, and other consultants. For other, more standardized OTC contracts, commonly referred to as “plain vanilla trades”, contracts can be entered into on a much more rapid and informal basis, e.g., via email.

For the limited purpose of wrapping your head around the world of derivatives, think of all derivatives as being in one of three broad categories: (1) exchange-traded derivatives (e.g., options on common stock and futures on pork belly); (2) standardized OTC contracts (e.g., your basic credit default swap); and (3) bespoke OTC contracts (transaction specific, often more complex instruments).

In fairness to Nocera, he’s not the only one weary of the third category of bespoke derivatives. But that doesn’t make his fears justified. So why do firms use custom made derivatives instead of just settling for an exchange traded derivative or a standardized swap? Despite uninformed opinions to the contrary, there are a lot of legitimate reasons for using custom derivatives. The most basic reason is what’s known as basis risk. The term refers to the risk that the difference between two rates will change. In the context of OTC derivatives, it usually refers to the risk that a hedge is imperfect. For example, a commodity user, like an airline, would like to lock in the price of jet fuel delivered to a terminal near an airport in northern California. However, the only exchange traded futures contracts available track the price of delivery to the Gulf Coast. While we would expect these two rates – the price of delivery to CA and the price of delivery to the Gulf Coast – to be correlated, there are all kinds of events, e.g., supply disruptions, that can affect one price without affecting the other. As such, using an exchange traded future would expose the airline to basis risk. By using a customized product, the airline can more perfectly hedge its exposure to the price of local fuel.

At this point, most of the bozo pundits would say, “just move all the customized trades onto an exchange!” That’s a fine idea, but it has the unfortunate feature of being impossible. In order to have an exchange, you need a lot of liquidity, or simply put, a lot of people trading perfectly fungible assets. The reason you need perfectly fungible assets is that it allows buyers and sellers to be matched on a rapid basis without any communication between them. Without a lot of people trading perfectly fungible assets, you don’t have a market where you can easily buy a new position or sell your current position, and therefore, you cannot have an exchange. Because bespoke derivatives are often one-off deals, hedging extremely specific risks, there is no market where they can be traded, for the simple reason that they are all unique and only useful to the parties to the original transaction. And so, bespoke derivatives are useful products that cannot always be substituted with exchange traded or standardized OTC products.

What Is Regulatory Capital?

There’s a lot of talk about regulatory capital in Obama’s proposal. So what is regulatory capital? In short, it has to do with how banks finance their operations. Banks are businesses. And like all businesses, they have investors that contribute money to the business. In the parlance of banking regulation, the money that investors contribute is called capital. This capital can come in various forms, despite the fact that it’s all cash. The form of the capital is determined by what the investor expects in return for his capital contribution. For example, equity capital comes from investors who expect to share in the profits of the bank. That is, after all of the bank’s expenses and debts are paid, the equity investors get their share of what, if anything, is left over. Capital could also come in the form of debt. The bank’s debt investors, commonly referred to as creditors, expect regular payments in return for their investment, regardless of whether or not the bank generates a profit. As such, they get paid before any of the equity investors get paid. Because of this, we say that debt is higher in the capital structure of a bank than equity. But of course, life is a lot more complicated than simple debt and equity. And so, banks make use of a broad range of financing that falls in different places along a continuum from pure senior debt (the top of the capital structure) to pure subordinated equity. As money gets generated by the bank’s activities, that money gets pushed down the bank’s capital structure, paying investors off in order of seniority.

In the magical world of academia, capital structure isn’t supposed to matter much. But as Michael Milken reminds us, in the real world, capital structure matters, a lot. Firms that finance their activities with a lot of debt will have high fixed obligations, since creditors don’t care if you make a profit or not. They invested on terms that assured them payment, come hell or high water. And while they might not be as intimidating as the Goodfellas, creditors have a lot of power over firms that fail to pay their debts. These powers range from seizing assets pledged as collateral to forcing bankruptcy upon the firm. Obviously, these kinds of events are disruptive to a firm’s business activities. And as this crisis has taught us, the business activities of banks are pretty important. Fully aware of this, the world developed what are known as regulatory capital requirements. What these requirements do is place restrictions on the capital structure of banks based on the riskiness of the bank’s activities. As you would expect, the rules that implement these restrictions are very complicated. But the general idea is fairly intuitive: as the riskiness of the bank’s activities increases, the bulk of the bank’s financing should move down the capital structure, towards equity. This makes sense, since a bank that is running a high risk operation shouldn’t be promising too many people regular income, since by definition, their cash flows are unstable. As such, a high risk bank should make greater use of equity, since equity investors only expect their share of the profits, if and when they appear.

Most of the developed world has adopted some version of the bank capital regulations known as the Basel Accords, written by the Bank For International Settlements. Under the Basel rules, assets are assigned a weight, which is determined by the asset’s riskiness. “No risk” assets, such as short term U.S. Treasuries, are assigned a weight of 0%. High risk assets can have weights over 100%. The rules then look to the capital of the bank and break it up into three Tiers: Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3. Tier 1 is comprised of pure equity and retained earnings, the absolute bottom of the capital structure; Tier 2 is comprised of financing that’s almost equity, or just above Tier 1 in the capital structure; and Tier 3 is comprised of short term subordinated debt, or the lowest part of the capital structure that can be fairly characterized as debt. Anything above Tier 3 doesn’t count as capital for the purposes of the rules.

When a bank buys an asset, they are generally required to assign a capital charge to that asset equal to 8% of the value of the asset multiplied by its risk weight. Half of the capital they set aside must come from Tier 1. So for a $100 loan with a risk weight of 50%, the bank that issued or bought the loan would need to set aside 8% x 50% x $100 = 8% x $50 = $4 worth of regulatory capital, at least half of which must come from Tier 1.

So regulatory capital requirements are a matching game between a firm’s assets and its capital structure. The more capital a firm has to set aside to purchase an asset, the fewer assets it can purchase. This means that heightened regulatory capital requirements will restrict a firm’s ability to generate returns on its capital. Well aware of this, Obama’s proposal uses regulatory capital as a tool to push firms away from certain practices. For example, as mentioned above, the proposal calls for increasing the capital charge for bespoke trades. It also threatens firms that are “too big to fail” with the spectre of overall heightened capital requirements. While Nocera thinks this is an empty threat, not everyone is so confident. But in any case, go read it yourself, at least the summary, and come to your own conclusions.

[IMAGES REMOVED BY UST; SEE REPORT LINK BELOW]

[IMAGES REMOVED BY UST; SEE REPORT LINK BELOW]