Introduction

Following up on yesterday’s article, in which I introduced an efficient method for clustering points in massive datasets, below is an algorithm that can actually identify macroscopic objects in massive datasets, with perfect precision. That is, it can cluster points into objects such that the clusters correspond perfectly to the actual objects in the scene, with no classification errors, and exactly the correct number of objects.

The goal of this work is to build up to an object identification and tracking algorithm, that can operate with an enormous number of observations, as an analog of my earlier object tracking algorithm, but extended to massive datasets, making use of my latest work.

The first step is to cluster the data using the algorithm I introduced yesterday, which will produce not only an initial set of clusters, but also a value called “delta”, that is the in-context minimum difference necessary to justify distinguishing between to two vectors. There’s a lot of thinking behind this, and it is part of the core of my work in information theory, but the big picture idea is, if we have two vectors and

, that are part of some dataset

, my algorithms will generate a value associated with

,

, such that if

, then

and

are distinct vectors, in the context of the dataset

.

If you’re interested, you can read a full explanation of the theory and mathematics of this process in my original article on A.I., “A New Model of Artificial Intelligence“.

Another property of the value delta, is that it quantizes distance in a dataset. That is, we can express the distance between two vectors as an integer multiple of delta, using the ceiling or floor operator. Now you could of course say, “so what”, since you can do that with any number, but the difference is, delta tells you how far apart things need to be in order to say they’re different in a particular context, which makes it a natural unit of measure for the dataset that generated the value of delta.

The algorithm below makes use of this insight, by doing the following:

First, we generate a value of delta by simply clustering the dataset using the method I introduced yesterday, which will produce additional local clustering. That is, the clusters are accurate, in that points clustered together are actually part of the same object, but the object is overly subdivided. Since the goal is to do object tracking, this is not ideal, and we’d like instead to have clean, macroscopic objects clustered together, that we can then track over some number of frames.

In order to accomplish this, as a second step, we begin with the first vector in the first cluster, which is the minimal element of that cluster. Then, we count the number of vectors that are within of this first, minimal element. After that, we count the number of vectors that are within

,

, and so on, up to a number of iterations that is calculated in the code, and likely to be modest in number.

If the dataset is comprised of actual objects, then as you get further away from the minimal element of the object, the number of new points should drop off suddenly at the boundary of the object –

Just imagine beginning in the center of a sphere, and proceeding outwards towards the perimeter, counting the number of points along the way. As you do this, the number of new points will increase at a reasonably steady rate, until you reach the perimeter, where the number of new points will drop off to basically zero.

This algorithm tracks the rate of change in new points as you increment the integer multiple of delta, and then finds the point at which the rate of increase drops off, and that’s the boundary of the object.

This is then repeated until the dataset is exhausted.

This could of course work using some other measure of distance, rather than delta, but the utility of this approach is that delta can be calculated quickly for any dataset, so unless you have a different number that you can quickly produce, that works for this purpose, you can’t use this algorithm, despite the fact that it will obviously work.

Application to Data

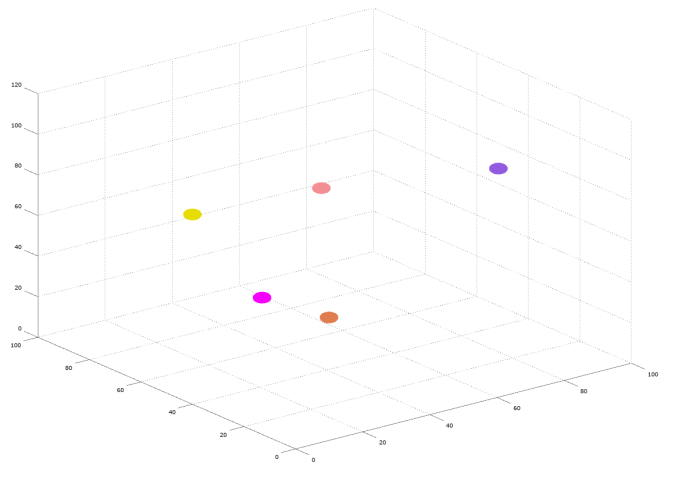

In this case, the dataset consists of 39,314 Euclidean 3-vectors, containing 5 statistical spheres.

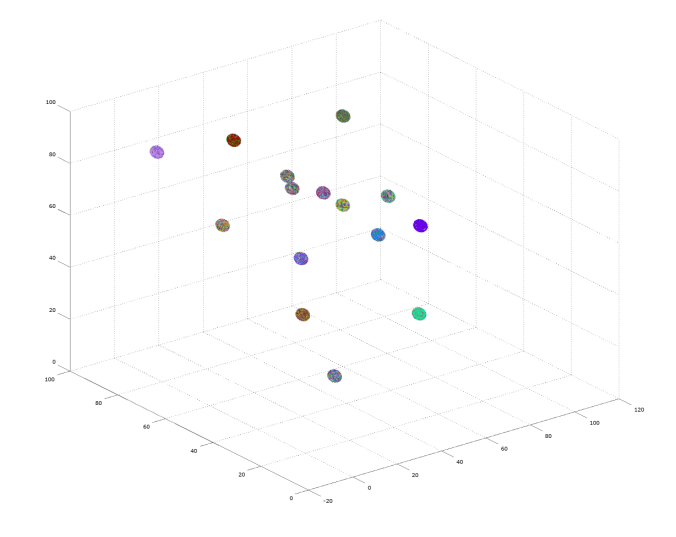

A dataset of five statistical spheres after being clustered.

The initial clustering took 37.2266 seconds, running on an iMac, with no errors, in that if two points are clustered together, then they are part of the same sphere.

However, as noted above, this process produces additional local clustering that we’d like to eliminate, since the goal is to identify and track macroscopic objects. You can visualize this using the image above, in which points colored the same are part of the same cluster, plainly showing multiple colors within the same sphere. The number of clusters produced in this first process is 1,660, suggesting significant local clustering, since there are only 5 spheres.

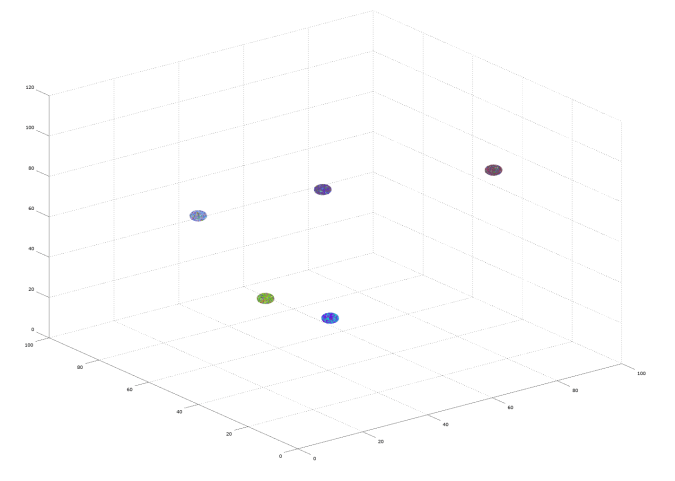

The dataset of five spheres after being subject to macro-clustering.

The next step is to use the value of delta generated in the first step, to try and consolidate these clusters into macroscopic objects.

This next round of clustering took 0.0396061 seconds, running on an iMac, again with perfect accuracy. Moreover, the number of clusters produced is 5, exactly the number of spheres in the dataset, implying that the performance is perfect.

Octave Code:

Full Library: