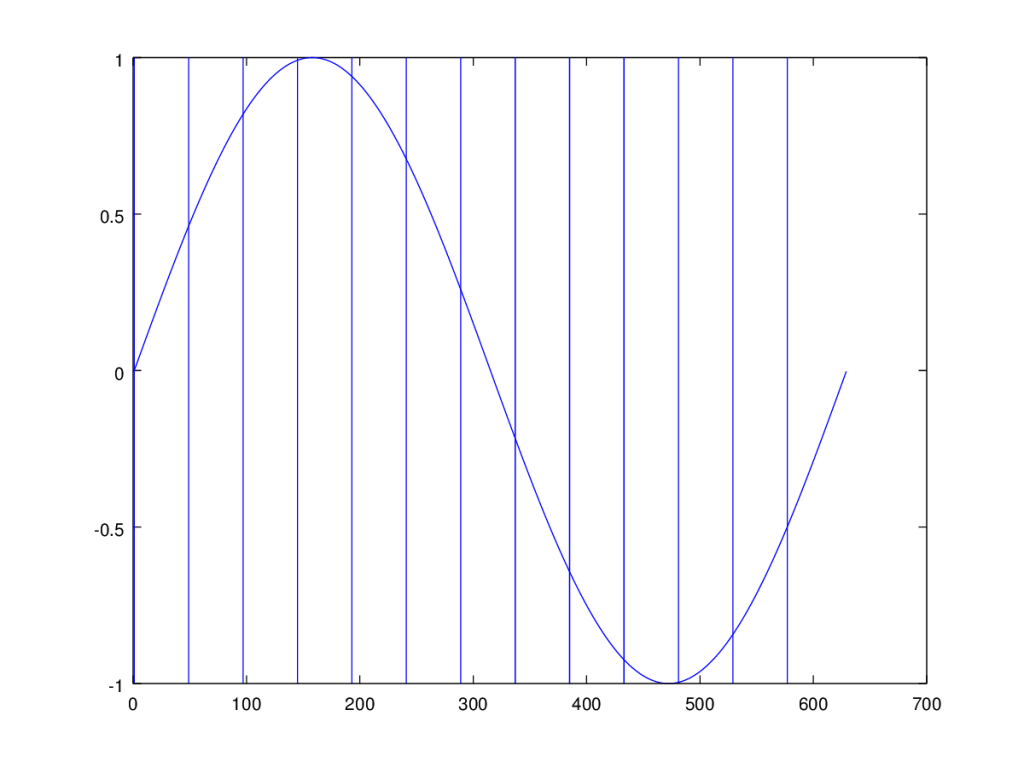

Revisiting the topic of periodicity, the first question I tried to answer is, given a point, how do you find the corresponding points in the following cycles of the wave? If for example, you have a simple sine wave, then this reduces to looking for subsequent points in the domain that have exactly the same range value. However, this is obviously not going to work if you have a complex wave, or if you have some noise.

You would be in this view looking for the straightest line possible across the range, parallel to the x-axis, that hits points in the wave, since those points will for a perfectly straight line, have exactly equal range values. So then the question becomes, using something like this approach, how do I compare two subsets of the wave, in the sense that, one could be better than the other, in that one more accurately captures some sub-frequency of the total wave. This would be a balancing act between the number of points captured, and the error between their respective values. For example, how do you compare two points that have exactly the same range value, and ten points that have some noise?

The Logarithm of a Vector

This led me to what is fairly described as vector entropy, in that it is a measure of diffusion that produces a vector quantity. And it seems plausible that maximizing this value will allow you to pull the best sets of independent waves from a total wave, though I’ve yet to test this hypothesis, so for now, I’ll just introduce the notion of vector entropy, which first requires defining the logarithm of a vector.

Defining the logarithm of a vector is straight forward, at least for this purpose:

If  , then

, then  , and

, and  .

.

That is, raising  to the power of the norm of

to the power of the norm of  produces the norm of

produces the norm of  , and both vectors point in the same direction. Note that because

, and both vectors point in the same direction. Note that because  , and

, and  , it follows that

, it follows that  .

.

This also implies a notion of bits as vectors, where the total amount of information is the norm of the vector, which is consistent with my work on the connections between length and information. It also implies that if you add two opposing vectors, the net information is zero. As a consequence, considering physics for a moment, two offsetting momentum vectors would carry no net momentum, and no net information, which is exactly how I describe wave interference.

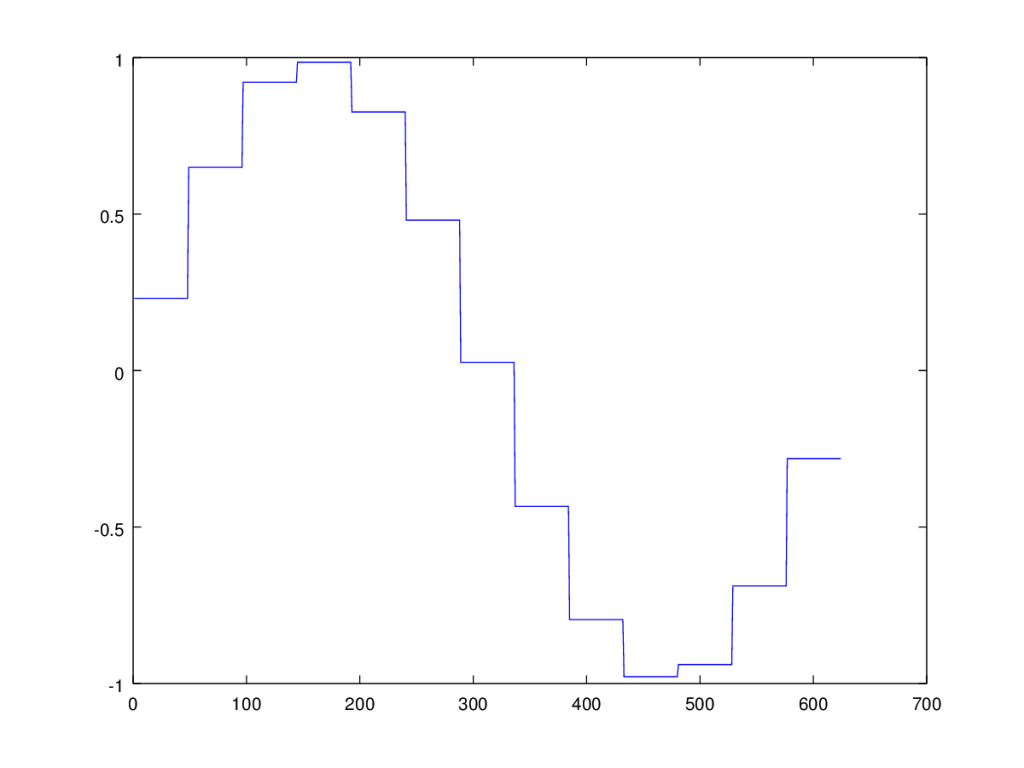

Vector Entropy

Now, simply read the wave from left to right (assuming a wave in the plane), and each point will define a  vector, in order. Take the vector difference between each adjacent pair of vectors, and take the logarithm of that difference, as defined above. Then take the vector sum over the resultant set of difference vectors. This will produce a vector entropy, and the norm of that vector entropy is the relevant number of bits.

vector, in order. Take the vector difference between each adjacent pair of vectors, and take the logarithm of that difference, as defined above. Then take the vector sum over the resultant set of difference vectors. This will produce a vector entropy, and the norm of that vector entropy is the relevant number of bits.

Expressed symbolically, we have,

Where  has units of bits.

has units of bits.

Lemma 1. The norm of  is maximized when all

is maximized when all  are equal in magnitude and direction.

are equal in magnitude and direction.

Proof. We begin by proving that,

is maximized when the norms of all  are equal. Assume this is not the case, and so there is some

are equal. Assume this is not the case, and so there is some  . We can restate

. We can restate  as,

as,

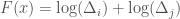

![\bar{H} = \sum_{\forall k \neq (i,j)}[\log(||\Delta_k||)] + \log(\Delta_i) + \log(\Delta_j).](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbar%7BH%7D+%3D+%5Csum_%7B%5Cforall+k+%5Cneq+%28i%2Cj%29%7D%5B%5Clog%28%7C%7C%5CDelta_k%7C%7C%29%5D+%2B+%5Clog%28%5CDelta_i%29+%2B+%5Clog%28%5CDelta_j%29.&bg=ffffff&fg=444444&s=0&c=20201002)

Now let  , and let

, and let  . Note that if

. Note that if  , then

, then  . Let us maximize

. Let us maximize  , which will in turn maximize

, which will in turn maximize  by taking the first derivative of

by taking the first derivative of  , with respect to

, with respect to  , which yields,

, which yields,

Setting  to zero, we find

to zero, we find  , which in turn implies that

, which in turn implies that  has an extremal point when the arguments to the two logarithm functions are equal to each other. The second derivative is negative for any positive value of

has an extremal point when the arguments to the two logarithm functions are equal to each other. The second derivative is negative for any positive value of  , and because

, and because  is the sum of the norm of two vectors,

is the sum of the norm of two vectors,  is always positive, which implies that

is always positive, which implies that  is maximized when

is maximized when  . Since we assumed that

. Since we assumed that  is maximized for

is maximized for  , we have a contradiction. And because this argument applies to any pair of vectors, it must be the case that all vectors have equal magnitudes.

, we have a contradiction. And because this argument applies to any pair of vectors, it must be the case that all vectors have equal magnitudes.

For any set of vectors, the norm of the sum is maximized when all vectors point in the same direction, and taking the logarithm does not change the direction of the vector. Therefore, in order to maximize  , it must be the case that all

, it must be the case that all  point in the same direction. Note that if all such vectors point in the same direction, then,

point in the same direction. Note that if all such vectors point in the same direction, then,

,

,

which completes the proof. □

Note that this is basically the same formula I presented in a previous note on spatial diffusion, though in this case, we have a vector quantity of entropy, which is, as far as I know, a novel idea, but these ideas have been around for decades, so it’s possible someone independently discovered the same idea.

, and a set of positional offsets

, where each

is a proper frequency, and each

is the distance from the starting point of the wave to where frequency

first appears in the total wave. This would create a juxtaposition of waves, just like you find in an audio file. Then, you just need a device that translates this representation into the relevant sensory phenomena, such as a speaker that takes the frequencies and articulates them as an actual sound. The thing is, this is even cleaner than an uncompressed audio file, because there’s no averaging of the underlying frequencies –