This is now a formal paper, available here.

It dawned on me yesterday that sorting a list of numbers is equivalent to minimizing the distance between adjacent entries in the list. Sorting has obviously been around for a long time, so this could easily be a known result, that perhaps even appears in college textbooks, that I simply forgot, but that’s not the point –

The point is, it suggests a more general notion of sorting that would apply to all mathematical objects for which there is a measure of distance  ,

,

where  is the set of objects in question. That is, if you can compare every pair of objects and map the difference between them to the real line, then you can define a partial order on the set in question, that minimizes the distance between adjacent pairs in some directed graph, and that doing so, is the abstract analog of sorting a list of numbers. The reason this is important, to me at least, is that it allows you to use a measure of entropy that I developed for planar waves, to be applied to arbitrary sets of objects that meet this requirement.

is the set of objects in question. That is, if you can compare every pair of objects and map the difference between them to the real line, then you can define a partial order on the set in question, that minimizes the distance between adjacent pairs in some directed graph, and that doing so, is the abstract analog of sorting a list of numbers. The reason this is important, to me at least, is that it allows you to use a measure of entropy that I developed for planar waves, to be applied to arbitrary sets of objects that meet this requirement.

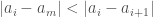

Lemma. A list of real numbers  is sorted, if and only if, the distance

is sorted, if and only if, the distance  is minimal for all

is minimal for all  .

.

Proof. Assume the list is sorted in ascending order, and that the lemma is false. Because the list is sorted, the distance  , must be minimal for

, must be minimal for  , since by definition, all other elements are greater than

, since by definition, all other elements are greater than  . By analogy, the distance

. By analogy, the distance  must also be minimal for

must also be minimal for  . Therefore it follows that there must be some

. Therefore it follows that there must be some  , for which either –

, for which either –

(1)  ,

,

or,

(2)  .

.

That is, because we have eliminated the first and last entries in the list, in order for the lemma to be false, there must be some pair of adjacent entries, and some third entry, with a distance to one of those two that is less than the distance between the pair itself. Because assuming  , or that

, or that  simply changes the indexes of the proof, it must be the case that

simply changes the indexes of the proof, it must be the case that  , which in turn contradicts the assumption that the list is sorted.

, which in turn contradicts the assumption that the list is sorted.

The proof in the case of a descending list is analogous.

Now we will prove by induction that if  is minimal for all

is minimal for all  , then the list is sorted:

, then the list is sorted:

Assume we start with a single item,  . Then, we want to insert some new item,

. Then, we want to insert some new item,  , in order to generate a list in ascending order, since a proof for descending order is analogous. Because there are only two items,

, in order to generate a list in ascending order, since a proof for descending order is analogous. Because there are only two items,  is the nearest neighbor of the new item

is the nearest neighbor of the new item  (i.e., the distance between

(i.e., the distance between  and

and  is minimal). If

is minimal). If  , then we insert

, then we insert  to the right of

to the right of  , and otherwise, we insert

, and otherwise, we insert  to the left of

to the left of  .

.

Now assume the lemma holds for some number of insertions  . It follows that this will imply a sorted list

. It follows that this will imply a sorted list  . If there is more than one nearest neighbor for a given insert (i.e., two items of equal distance from the insert item) that are both equal in value, then we find either the leftmost such item, or the rightmost such item, depending upon whether the inserted item is less than its nearest neighbor, or greater than its nearest neighbor, respectively. If the insert is equidistant between two unequal adjacent items, then we insert it between them.

. If there is more than one nearest neighbor for a given insert (i.e., two items of equal distance from the insert item) that are both equal in value, then we find either the leftmost such item, or the rightmost such item, depending upon whether the inserted item is less than its nearest neighbor, or greater than its nearest neighbor, respectively. If the insert is equidistant between two unequal adjacent items, then we insert it between them.

Now assume we are to insert item  , which will be insertion number

, which will be insertion number  . Further, assume that following this process causes the resultant list of

. Further, assume that following this process causes the resultant list of  items to be unsorted, solely as a result of this insertion (note we assumed that the list is sorted beforehand), and further, assume that the indexes are such that

items to be unsorted, solely as a result of this insertion (note we assumed that the list is sorted beforehand), and further, assume that the indexes are such that  is the correct set of indexes for the sorted list prior to the insertion of

is the correct set of indexes for the sorted list prior to the insertion of  .

.

Now assume the process above places  at the front of the list. Because the list is unsorted, it must be that

at the front of the list. Because the list is unsorted, it must be that  , but this is impossible, according to the process above, which would place it to the right of

, but this is impossible, according to the process above, which would place it to the right of  . Now assume the process above places

. Now assume the process above places  at the end of the list. Because the list is unsorted, it must be that

at the end of the list. Because the list is unsorted, it must be that  , but again, the process above dictates an insertion to the left.

, but again, the process above dictates an insertion to the left.

Therefore, since by assumption the list is unsorted, it must be the case that  is inserted between two items in the list

is inserted between two items in the list  . By the process described above, it must also be the case that the distance to at least one of them is minimal, so assume that

. By the process described above, it must also be the case that the distance to at least one of them is minimal, so assume that  is the nearest neighbor of

is the nearest neighbor of  . Again, since by assumption, the list is out of order, it must be the case that either –

. Again, since by assumption, the list is out of order, it must be the case that either –

(1)  ,

,

or

(2)  .

.

In case (1), again, the process above dictates insertion to the left of  , which eliminates this case as a possibility. In case (2), it must be that

, which eliminates this case as a possibility. In case (2), it must be that  is the nearest neighbor of

is the nearest neighbor of  , which leads to a contradiction. The cases where

, which leads to a contradiction. The cases where  is the nearest neighbor of

is the nearest neighbor of  are analogous, which completes the proof. □

are analogous, which completes the proof. □

Though there are some wrinkles I haven’t worked out, this alludes to a linear runtime sorting algorithm for sorting not only real numbers, but anything capable of comparison that maps to real numbers. This is because the nearest neighbor algorithm itself can be fully vectorized into a linear runtime algorithm on a sufficiently parallel machine. The problem is, some of the steps described above, cannot be vectorized, at least in Matlab. However, I think a working algorithm not covered by the proof above, at least as stated, would always look for the nearest unequal neighbor, that a given item is less than. That is, for a given item, the algorithm returns an item that is strictly greater the item in question (call this, “the least larger neighbor”). Then you simply have a matrix, with a number of columns equal to the number of items, and a number of rows, also equal to the number of items, which represents in this case a directed graph. Then, for  , if the least larger neighbor is

, if the least larger neighbor is  , you simply set all entries in row

, you simply set all entries in row  to zero, save for column

to zero, save for column  , which you set to one, denoting an edge from

, which you set to one, denoting an edge from  to

to  , which is no different than a sorted linked list.

, which is no different than a sorted linked list.

Attached is Octave code that implements this algorithm (not the one from the proof), which seems to work, though I have not proved that it works just yet. It’s set up to sort unique lists of numbers, so if you have duplicates in your list, simply insert them after the fact, which again takes  steps on a vectorized machine, by simply searching for each duplicate entry, and inserting it to the left or right of its copy. This produces a sorting algorithm that has a worst case

steps on a vectorized machine, by simply searching for each duplicate entry, and inserting it to the left or right of its copy. This produces a sorting algorithm that has a worst case  runtime on a parallel machine, and I’ll follow up with a proof that it works (assuming it does). If you implement the minimum operator in

runtime on a parallel machine, and I’ll follow up with a proof that it works (assuming it does). If you implement the minimum operator in  parallel steps, which can be done by successively taking the difference between adjacent terms, and deleting the left hand terms that produce a positive difference (i.e., if a – b is positive, then a cannot be the minimum element), then the sorting algorithm has a run time of

parallel steps, which can be done by successively taking the difference between adjacent terms, and deleting the left hand terms that produce a positive difference (i.e., if a – b is positive, then a cannot be the minimum element), then the sorting algorithm has a run time of  parallel steps, which assumes no duplicate entries.

parallel steps, which assumes no duplicate entries.

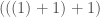

Returning again to the measure of entropy linked to above, you can view it as measuring how much information you need to represent a set of numbers using recursion. For example, if you sort the set of numbers  , then you can express the set as a sequence

, then you can express the set as a sequence  , where you begin with

, where you begin with  , and add each entry in the vector in order, i.e.,

, and add each entry in the vector in order, i.e.,  . If you first sort the set of numbers in question, you will minimize the amount of information required to encode the set of numbers as a recursive sequence, because it takes less information to encode smaller numbers than larger numbers. Note that this also requires less information than encoding the set itself. This suggests an equivalence between sorting a set of numbers, and minimizing the amount of information required to represent that set using recursion of this form.

. If you first sort the set of numbers in question, you will minimize the amount of information required to encode the set of numbers as a recursive sequence, because it takes less information to encode smaller numbers than larger numbers. Note that this also requires less information than encoding the set itself. This suggests an equivalence between sorting a set of numbers, and minimizing the amount of information required to represent that set using recursion of this form.

You can then generalize this to vectors, and encode a set of vectors, as a sequence of vectors expressed analogously in some order.

All of this lead to the following conjectures, that I’m simply not taking the time to even attempt to prove:

Conjecture 1. There is no sorting algorithm that can generate a total order on a set of unique numbers in less than  steps;

steps;

Conjecture 2. There is no sorting algorithm that can generate a partial order on a set of numbers (allowing for duplicates) in less than  steps;

steps;

Conjecture 3. There is no sorting algorithm that can generate a total order on a set of numbers (allowing for duplicates) in less than  steps,

steps,

in each case, where  is the number of items in the set.

is the number of items in the set.

from the dataset, and the set of points near

have the same classifier as

, then the nearest neighbor algorithm can be modified slightly to produce perfect accuracy. And I’ve introduced a ton of software that allows you to find that appropriate distance, which I call

. The reason this sort of new approach (I came up with this a while ago) is interesting, is because it doesn’t require any supervision –

, as opposed to a training step.

runtime, and the accuracy is consistently better than nearest neighbor. Note that you can also construct an

runtime algorithm using the code attached to my paper Sorting, Information, and Recursion.