The Cart Before The Horse

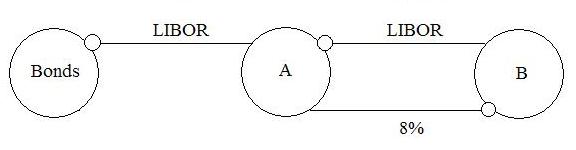

There has been a lot of chatter about the systemic risks posed by derivatives, particularly credit default swaps. Rather than offer any formal method of evaluating an enormously complicated question, pundits wield exclamation points and false inferences to distract from the glaring holes in their logic. Below I will not offer any definite answers to any questions about the systemic risks posed by derivatives. Rather, I will describe what I think is a reasonable and useful framework for analyzing systemic risks posed by derivatives. Unfortunately for some, this will involve the use of mathematics. And while the math used is fairly elementary, the concepts are not. This is especially true of the last section. That said, even if you do not fully understand the entirety of this article, one thing should be clear: questions about systemic risk are complex and anyone who gives declarative answers to such questions is almost certain to have no idea what they are talking about.

Risk Magnification And Syndication

As discussed here, derivatives operate by creating and allocating risks that did not exist before the two parties entered into the transaction. That is an unavoidable fact. Moreover, there is no physical limit to the notional amount of any given contract or the number of derivative contracts that parties can enter into. It is entirely up to them. That said, derivatives can be used to negate risks that parties were already exposed to in exchange for assuming other risks, thereby acting as a risk-switching/risk-transferring device. So, a corollary of these observations is that derivatives could be used to create unlimited amounts of risk but through that risk creation they could be used to negate an unlimited amount of risk that parties are already exposed to and thereby effectively “transfer” an unlimited amount of risk to those willing to be exposed to it.

Practically speaking, there is a limit to the amount of risk that can be created using derivatives. This limit exists for a very simple reason: the contracts are voluntary, and so if no one is willing to be exposed to a particular risk, it will not be created and assigned through a derivative. Like most market participants, derivatives traders are not in engaged in an altruistic endeavor. As a result, we should not expect them to engage in activities that they don’t expect to be profitable. Therefore, we can be reasonably certain that the derivatives market will create only as much risk as its participants expect to be profitable. Whether their expectations are correct is an entirely different matter, and any criticism on that front is not unique to derivatives traders. Rather, the problem of flawed expectations permeates all of human decision making.

Even if we ignore the practical limits to the creation of risk, derivatives allow for unlimited syndication of risk. That is, there is no smallest unit of risk that can be transferred. Consequently, any fixed amount of risk can be syndicated out to an arbitrarily large number of parties, thereby minimizing the probability that any individual market participant will fail as a result of that risk.

Finally, we should ask ourselves, what does the term systemic risk even mean? The only thing it can mean in the context of derivatives is that the obligations created by two parties will have an effect on at least one other third party. So, even assuming that derivatives create such a “problem,” how is this “problem” any different than that created by a landlord who plans to pay a contractor with the rent he receives from his tenants? It is not.

A Closer Look At Risk

As stated here, my own view is that risk is a concept that has two components: (i) the occurrence of an event and (ii) a magnitude associated with that event. This allows us to ask two questions: What is the probability of the event occurring? And if it occurs, what is the expected value of its associated magnitude? We say that P is exposed to a given risk if P expects to incur a gain/loss if the risk-event occurs. As is evident, under this rubric, that whole conversation above was grossly imprecise. But that’s ok. Its import is clear enough. From here on, however, we will tolerate no such imprecision.

Identifying And Defining Risks

Using the definition above, let’s try to define one of the risks that all parties who sold protection on ABC’s series I bonds through a CDS that calls for physical delivery are exposed to. This will allow us to begin to understand the systemic risk that such credit default swaps create. There is no hard rule about how to go about doing this. If we do a poor job of identifying and defining the relevant risks, we will have a poor understanding of those relevant risks. However, common sense tells us that any protection seller’s risk exposure is going to have something to do with triggering a payout under a CDS. So, let’s define the risk-event as any default on ABC series I bonds. For simplicities sake, let’s limit our definition of default to ABC’s failure to pay interest or principle. So, our risk-event is: ABC fails to pay interest or principle on any of its bonds. But what is our risk-magnitude? Since we are trying to define a risk that protection sellers are exposed to, our associated magnitude should be the basis upon which all payments by protection sellers are made. So, we will define the risk-magnitude as  where

where  is the price of an ABC series I bond after the risk-event (default) occurs and

is the price of an ABC series I bond after the risk-event (default) occurs and  is the par value of an ABC series I bond. For example, if ABC’s series I bonds are trading at 30 cents on the dollar after default,

is the par value of an ABC series I bond. For example, if ABC’s series I bonds are trading at 30 cents on the dollar after default,  and a protection seller would have to payout 70 cents for every dollar of notional amount. The amount that bonds trade at after a default is called the recovery value.

and a protection seller would have to payout 70 cents for every dollar of notional amount. The amount that bonds trade at after a default is called the recovery value.

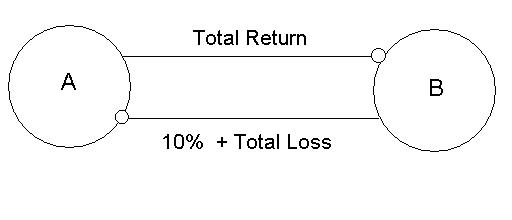

One Man’s Garbage Is Another Man’s Glory

When one party to a derivative makes a payment, the other receives it. That seems simple enough. But it follows that if we consider only those payments made under the derivative contract itself, the net position of the two parties is unchanged over the life of the agreement. That is, derivatives create zero-sum games and simply shift and reallocate money that already existed between the two parties. So in continuing with our example above, it follows that we’ve also defined a risk that buyers of protection on ABC series I bonds are exposed to. However, protection buyers have positive exposure to that risk. That is, if ABC defaults, protection buyers receive money.

Exposure To Risk And Settlement Flow Analysis

If our concept of exposure is to have any real economic significance, it must take into account the concept of netting. So, we define the exposure of  to the risk-event defined above as the product of (i) the net notional amount of all credit default swaps naming ABC series I bonds as a reference obligation to which

to the risk-event defined above as the product of (i) the net notional amount of all credit default swaps naming ABC series I bonds as a reference obligation to which  is a counterparty, which we will call

is a counterparty, which we will call  , and (ii)

, and (ii)  . The net notional amount is simply the difference between the total notional amount of protection bought and the total notional amount of protection sold by

. The net notional amount is simply the difference between the total notional amount of protection bought and the total notional amount of protection sold by  . So, if

. So, if  is a net seller of protection,

is a net seller of protection,  will be negative and therefore its exposure,

will be negative and therefore its exposure,  , will be either negative or zero.

, will be either negative or zero.

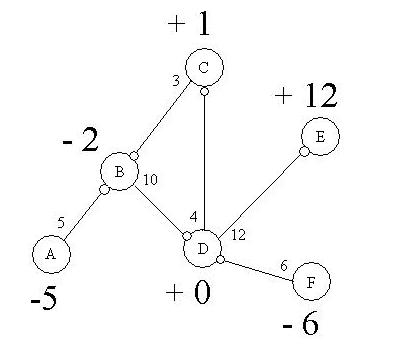

Because the payments between the two counterparties of each derivative net to zero, it follows that the sum of all net notional amounts is always zero. That is, if there are  market participants,

market participants,  . The total notional amount of the entire market is given by

. The total notional amount of the entire market is given by  . This is the figure that is most often reported by the media. As is evident, it is impossible to determine the economic significance of this number without first knowing the structure of the market. That is, we must know how much is owed and to whom. However, after we have this information, we can choose different recovery values and then calculate each party’s exposure. This would enable us to determine how much cash each participant would have to set aside for a default at various recovery values (simply calculate each party’s exposure at the various recovery values).

. This is the figure that is most often reported by the media. As is evident, it is impossible to determine the economic significance of this number without first knowing the structure of the market. That is, we must know how much is owed and to whom. However, after we have this information, we can choose different recovery values and then calculate each party’s exposure. This would enable us to determine how much cash each participant would have to set aside for a default at various recovery values (simply calculate each party’s exposure at the various recovery values).

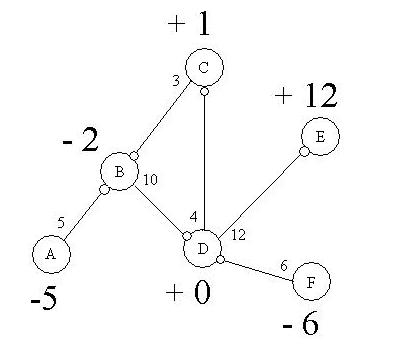

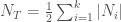

Let’s consider a concrete example. In the diagram below, an edge coming from a participant represents protection sold by that participant and consequently an incoming edge represents protection bought by that participant. The amounts written beside these edges represent the notional amount of protection bought/sold. The amounts written beside the nodes represent the net notional amounts.

In the example above, D is a dealer and his net notional amount is zero, and therefore his exposure to the risk-event is  . As is evident, we can vary the recovery value to determine what each market participant’s exposure would be in that case. We could then consider other risk-events that occur in conjunction with any given risk-event. For example, we could consider the conjunctive risk-event “ABC defaults and B fails to pay under any CDS” (in which case D’s exposure would not be zero) or any other variation that addresses meaningful concerns. For now, we will focus on our single event risk for explanatory purposes. But even if we restrict ourselves to single event risks, there’s more to a CDS than just default. Collateral will move through the above system dynamically throughout the lives of the contracts. In order to understand how we can analyze the systemic risks posed by the dynamic shifting of collateral, we must first examine what it is that causes collateral to be posted under a CDS.

. As is evident, we can vary the recovery value to determine what each market participant’s exposure would be in that case. We could then consider other risk-events that occur in conjunction with any given risk-event. For example, we could consider the conjunctive risk-event “ABC defaults and B fails to pay under any CDS” (in which case D’s exposure would not be zero) or any other variation that addresses meaningful concerns. For now, we will focus on our single event risk for explanatory purposes. But even if we restrict ourselves to single event risks, there’s more to a CDS than just default. Collateral will move through the above system dynamically throughout the lives of the contracts. In order to understand how we can analyze the systemic risks posed by the dynamic shifting of collateral, we must first examine what it is that causes collateral to be posted under a CDS.

We’re In The Money

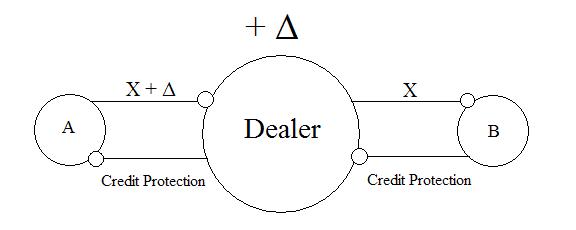

CDS contracts come in and out of the money to a party based on the price of protection. If a party is out of money, the typical market practice is to require that party to post collateral. For example, if I bought protection at a price of 50bp, and suddenly the price jumps to 100bp, I’m in the money and my counterparty is out of the money. Thus, my counterparty will be required to post collateral. We can view the price of protection as providing an implied probability of default. Exactly how this is done is not important. But it should be clear that there is a connection between the cost of protecting debt and the probability of default on that debt (the higher the probability the higher the cost). Thus, as the implied probability of default changes over the life of the agreement, collateral will change hands.

Collateral Flow Analysis

In the previous sections, we assumed that the risk-event was certain to occur and then calculated the exposures based on an assumed recovery value. So, in effect, we were asking “what happens when parties settle their contracts at a given recovery value?” But what if we want to consider what happens before any default actually occurs? That is, what if we want to consider “what happens if the probability of default is  ?” Because collateral will be posted as the price of protection changes over the life of the agreement and the price of protection provides an implied probability of default, it follows that the answer to this question should have something to do with the flow of collateral.

?” Because collateral will be posted as the price of protection changes over the life of the agreement and the price of protection provides an implied probability of default, it follows that the answer to this question should have something to do with the flow of collateral.

Continuing with the ABC bond example above, we can examine how collateral will move through the system by asking two questions: (i) what is the implied probability of the risk-event (ABC’s default) occurring and (ii) what is the expected value of the risk-magnitude (the basis upon which collateral payments are made). As discussed above, the implied probability of default will change over the life of the agreement, which will in turn affect the flow of collateral in the system. Since our goal in this section is to test the system’s behavior at different implied probabilities of default, the expected value of our risk-magnitude should be a function of an assumed implied probability of default. So, we define the expected value of our risk-magnitude as  where

where  is our assumed implied probability of default and

is our assumed implied probability of default and  is defined as it is above. It follows that this analysis will break CDS contracts into categories according to the price at which they were entered into. That is, you can’t ask how much something changed without first knowing what it was to begin with.

is defined as it is above. It follows that this analysis will break CDS contracts into categories according to the price at which they were entered into. That is, you can’t ask how much something changed without first knowing what it was to begin with.

Assume that  entered into CDS contracts at

entered into CDS contracts at  different prices. For example, he entered into four contracts at 20 bp and eight contracts at 50bp, and no others. In this case,

different prices. For example, he entered into four contracts at 20 bp and eight contracts at 50bp, and no others. In this case,  . For each

. For each  , assign an arbitrary ordering,

, assign an arbitrary ordering,  , to the sets of contracts that were entered into at different prices by

, to the sets of contracts that were entered into at different prices by  . In the example where

. In the example where  , we could let

, we could let  be the set of eight contracts entered into at 50bp and let

be the set of eight contracts entered into at 50bp and let  be the set of four contracts entered into at 20 bp. Each of these sets will have a net notional amount and an implied probability of default (since each is categorized by price). Define

be the set of four contracts entered into at 20 bp. Each of these sets will have a net notional amount and an implied probability of default (since each is categorized by price). Define  as the net notional amount of the contracts in

as the net notional amount of the contracts in  and

and  as the implied probability of default of the contracts in

as the implied probability of default of the contracts in  for each

for each  . We define the expected exposure of

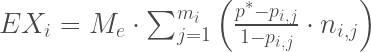

. We define the expected exposure of  as:

as:

.

.

Note that when  ,

,

.

.

That is, this is a generalized version of the settlement analysis above, and when we assume that default is certain, collateral flow analysis reduces to settlement flow analysis.

So What Does That Awful Formula Tell Us?

A participant’s expected exposure is a reasonable estimate for the amount of collateral that will be posted or received by that participant at an assumed implied probability of default. The exact amount of collateral that will be posted or received under any contract will be determined by the terms of that contract. As a result, our model is approximate and not exact. However, the direction that collateral moves in our model is exact. That is, if a party’s expected exposure is negative, it will not receive collateral, and if it is positive, it will not post collateral. It also shows that even if a party is completely hedged in the event of a default, it is possible that it is not completely hedged to posting collateral. That is, even if it bought and sold the same notional amount of protection, it could have done so at different prices.

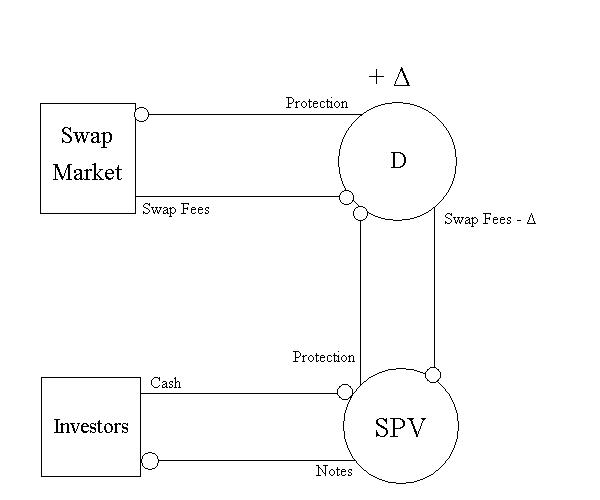

; pay them $100 in principle at the time at which the underlying CDS expires; with both promises conditioned upon the premise that ABC does not trigger an event of default, as that term is defined in the underlying CDS. In short, D has passed the cash flows from the Treasury/CDS package onto investors, in exchange for pocketing a fee (

). As noted above, the cash flows from this package are very similar to the cash flows received from ABC bonds. As a result, we call the notes issued by D synthetic bonds.

, where the notional amount of protection sold on each is

and the total notional amount is

. Rather than maintain exposure to all of these swaps, D could pass the exposure onto investors by issuing notes keyed to the performance of the swaps. The transaction that facilitates this is called a synthetic collateralized debt obligation or synthetic CDO for short. There are many transactions that could be categorized fairly as a synthetic CDO, and these transactions can be quite complex. However, we will explore only a very basic example for illustrative purposes.

dollars. D sets up an SPV, funds it with the money from the investors, and buys

dollars worth of protection on

for each

from the SPV. That is, D hedges all of his positions with the SPV. The SPV takes the money from the investors and invests it. For simplicity’s sake, assume that the SPV invests in the same Treasuries mentioned above. The SPV then issues notes that promise to: pay investors their share of

dollars after all underlying swaps have expired, where L is the total notional amount of protection sold by the SPV on entities that triggered an event of default; and pay investors their share of annual interest, in amount equal to

, where

is the sum of all swap fees received by D.