When you have a known set or population generally, with some known measurable traits, it’s a natural tendency to attribute the properties of that set, to new observations that qualify for inclusion in that set. In some contexts, this is deductively sound, and is not subject to uncertainty at all. For example, we know that the set of prime numbers have no divisors other than themselves and  . And so as a consequence, once we know that a number is included in the set of prime numbers, then it must be the case that any property that applies to all prime numbers, also applies to this new prime number. However, observation of course goes beyond mathematics, and you could for example be dealing with a population of genomes, with some known measurable property. Now given a new genome that qualifies for inclusion in this population, how can we be sure that the property of the population also holds for the new observation? There is no deductive reason for this, and instead it is arguably statistical, in that we have a population with some known property, which is universal in the known population, and we have some new observation that qualifies for inclusion in that population, under some criteria. Even if the criteria for inclusion in the population is directly measurable in the genome itself (e.g., an A at index

. And so as a consequence, once we know that a number is included in the set of prime numbers, then it must be the case that any property that applies to all prime numbers, also applies to this new prime number. However, observation of course goes beyond mathematics, and you could for example be dealing with a population of genomes, with some known measurable property. Now given a new genome that qualifies for inclusion in this population, how can we be sure that the property of the population also holds for the new observation? There is no deductive reason for this, and instead it is arguably statistical, in that we have a population with some known property, which is universal in the known population, and we have some new observation that qualifies for inclusion in that population, under some criteria. Even if the criteria for inclusion in the population is directly measurable in the genome itself (e.g., an A at index  ), you cannot be sure that the property actually holds, unless it follows directly from that measurement. More generally, unless inclusion in a given set is determined by a given measurement, and the property asserted of all elements in the set follows deductively from that measurement, you cannot with certainty attribute that property to some new observation.

), you cannot be sure that the property actually holds, unless it follows directly from that measurement. More generally, unless inclusion in a given set is determined by a given measurement, and the property asserted of all elements in the set follows deductively from that measurement, you cannot with certainty attribute that property to some new observation.

Put all of that aside for a moment, and let’s posit some function that allows you to generate a set, given a single element. If that function truly defines and generates a unique set, then applying that function to the elements of the generated set, should not produce new elements, and should instead produce exactly the same set. Said otherwise, it shouldn’t matter what element I start with, if our function defines a unique set. To create a practical example, view the set in question as a cluster taken from a dataset. This is quite literally a subset of the dataset. There must be in this hypothetical a function that determines whether or not an element of the dataset is in a given cluster. Let’s call that function  , and assume that

, and assume that  is either

is either  or

or  , indicating that the element

, indicating that the element  is either not in the cluster, or in the cluster, associated with element

is either not in the cluster, or in the cluster, associated with element  , respectively. That is,

, respectively. That is,  , when applied to all

, when applied to all  in the dataset, will generate a cluster for

in the dataset, will generate a cluster for  . Now for each

. Now for each  in the cluster associated with

in the cluster associated with  , calculate

, calculate  over all

over all  in the dataset. This will generate another cluster for every element of the original cluster associated with

in the dataset. This will generate another cluster for every element of the original cluster associated with  .

.

For each such cluster, count the number of elements that are included in the original cluster associated with  . The total count of such elements, is a measure of the inter-connectedness of the original cluster associated with

. The total count of such elements, is a measure of the inter-connectedness of the original cluster associated with  , since these are the elements that are generated by our function, given a new starting point, but are not new. Now count the number of elements that are not included in the original cluster associated with

, since these are the elements that are generated by our function, given a new starting point, but are not new. Now count the number of elements that are not included in the original cluster associated with  , these are new elements not in the original cluster. Viewed as a graph, treating each element of the original cluster for

, these are new elements not in the original cluster. Viewed as a graph, treating each element of the original cluster for  as a vertex, we would then have a set of edges that mutually connect elements of the original cluster for

as a vertex, we would then have a set of edges that mutually connect elements of the original cluster for  , and then a set of edges that go outside that cluster. If there are no edges coming out of the original set of elements in the cluster for

, and then a set of edges that go outside that cluster. If there are no edges coming out of the original set of elements in the cluster for  , then

, then  defines a perfectly self-contained set, that will always produce the same set, regardless of the element that we start with. More generally, you’re producing an analogous set for each element of a given set. Intuitively, the more self-contained that original set is, under this test, the more confident we are that the properties of the elements of that set are attributable to elements that qualify for inclusion in that set, for the simple reason that it is disconnected, quite literally, from all other sets. If a set is not self-contained, then it is by definition associated with other sets that could have other properties.

defines a perfectly self-contained set, that will always produce the same set, regardless of the element that we start with. More generally, you’re producing an analogous set for each element of a given set. Intuitively, the more self-contained that original set is, under this test, the more confident we are that the properties of the elements of that set are attributable to elements that qualify for inclusion in that set, for the simple reason that it is disconnected, quite literally, from all other sets. If a set is not self-contained, then it is by definition associated with other sets that could have other properties.

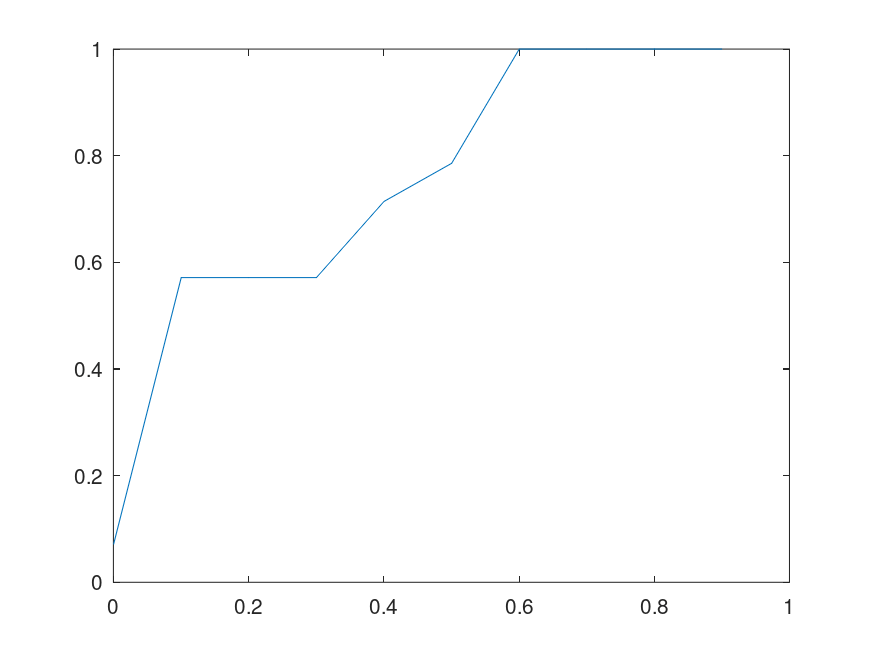

We can make this rigorous, using the work I presented in, Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty [1]. Specifically, your intuitive uncertainty in the attribution of properties of a set to new observations that qualify for inclusion in the set, increases as a function of the number of outbound edges. Similarly, your intuitive uncertainty decreases as a function of the number of mutually connective edges. We can measure uncertainty formally if we can express this in terms of the Shannon Entropy. As such, assign one color to the edges that are mutually connective, and assign a unique color for every other remaining vertex (i.e., element of the set). So if an element  of the original cluster for

of the original cluster for  connects to some external element

connects to some external element  , then the edge connecting

, then the edge connecting  to

to  will have a unique color assigned to

will have a unique color assigned to  . As such, all edges that connect to

. As such, all edges that connect to  will have the same color. If instead

will have the same color. If instead  connects to another element of the original cluster

connects to another element of the original cluster  , then it will have a different color, that is common to all mutually connective edges. As such, we will have two categories of colors, one color for all mutually connective edges, and a set of colors for all outbound edges. This will create a distribution of colors. Take the entropy of that distribution, and that will be your Uncertainty,

, then it will have a different color, that is common to all mutually connective edges. As such, we will have two categories of colors, one color for all mutually connective edges, and a set of colors for all outbound edges. This will create a distribution of colors. Take the entropy of that distribution, and that will be your Uncertainty,  . So if for example, all of the edges are mutually connective, they will have a single color, and therefore an entropy and Uncertainty of

. So if for example, all of the edges are mutually connective, they will have a single color, and therefore an entropy and Uncertainty of  . Let

. Let  be the total number of edges, i.e., mutually connective and outbound edges, and let

be the total number of edges, i.e., mutually connective and outbound edges, and let  be the number of edge colors. Information is in this case given by

be the number of edge colors. Information is in this case given by  (See, [1] generally). Knowledge is then simply

(See, [1] generally). Knowledge is then simply  .

.

One interesting note, that comes up every time I’ve worked on epistemology, is that if these results are empirically true (and as it turns out the results in [1] are in fact empirically true), it implies that our theory of knowledge itself is subject to improvement, separate and apart from the knowledge we obtain from experiment and deduction. This branch of what I suppose is philosophy therefore quantifies the knowledge that we obtain from empirical results. This study seems similar to physics, in that the results are axiomatic, and then empirically tested. In contrast, mathematical knowledge is not subject to uncertainty at all. And as a result, this work suggests that empiricism requires the careful and empirical study of knowledge itself, separate and apart from any individual discipline. Said otherwise, this work suggests, that empiricism is itself a science, subject to testing and improvement.