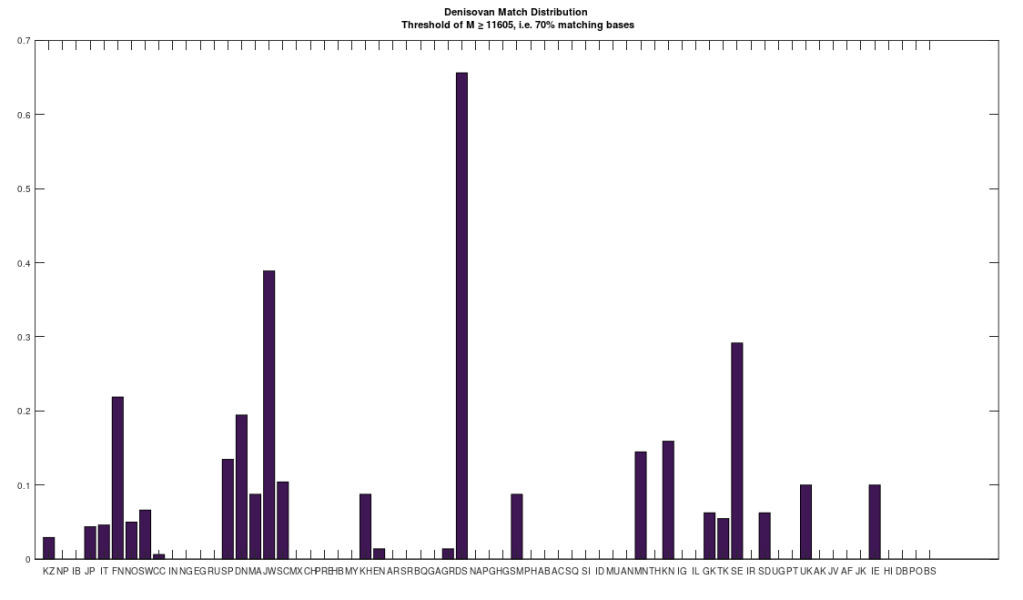

I’m in the process of unpacking the history of humanity using my machine learning software, and as part of that process, I decided to take a closer look at Denisovans. Specifically, many modern populations have individuals that are a 70% match to Denisovans. In particular, the Jews and Finns have large populations of people that are a 70% match. Below is a distribution that shows a normalized percentage of each population that is at least a 70% match to the Denisovans. The x-axis shows the acronym for the particular population, and all of the acronyms can be found at the end of my paper, A New Model of Computational Genomics [1]. You can also find all the software you need to run these experiments, in addition to the related technical information on alignment, process, etc., in [1].

The natural question is, are all Denisovans the same? Or do they have a unique history of their own? Denisovan remains are generally found in Asia. However, as you can see above, there are modern populations in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, that all contain matches to Denisovans. This suggests at least the possibility, that Denisovans have a unique history, that could predate human language altogether. The process I used to test this question is straightforward: First, I found all genomes that are at least a 70% match to at least one Denisovan genome. Then, I constructed clusters, as a second test, like the one below for the Swedish, effectively counting what percentage of each Denisovan population matched to the Swedish Denisovans. As you can see, the Swedish Denisovans are plainly related to the Norwegian Denisovans (which is not surprising based upon geography), though they’re also related to the Chinese Denisovans. Why? Well, Denisovan fossils are generally found in Asia, so this not surprising either.

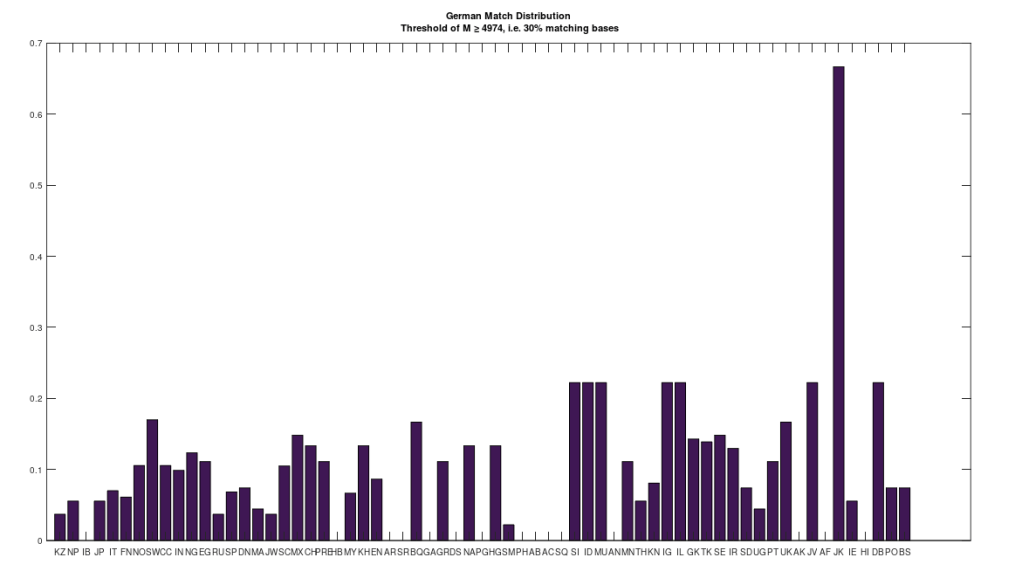

This is all very interesting on its own, but what’s far more interesting, is that when I tested the distribution of German Denisovans, they failed to match to any of the actual Denisovan genomes. That is, the German Denisovans (a modern population) failed to match to any of the actual ancient Denisovans in the second test. At first I thought I had made a mistake in the code, but I then isolated the Denisovan row of the dataset that the modern Germans match to, and it’s row 378 in the dataset attached below. However, this Denisovan genome itself does not match to any of the other Denisovan genomes, even at 30% of the genome. This suggests that row 378 of the dataset below, is not Denisovan, and is instead, an otherwise unknown species, that seems to be most related to people in the Jharkhand region of India, based upon the chart below, that shows the distribution of matches at 30% of the genome. Note that all of these genomes are taken from the National Institute of Health Database, and the dataset includes provenance files for all genomes, with links to the NIH Database.

It is of course possible that this genome would map to some other Denisovan genome not included in the dataset. However, I would instead wager that this genome is a very early Neanderthal, since it is a match to some Neanderthals at 30%. I think this find, at a minimum, suggests that archeology is limited in some sense, since it doesn’t look to the genome. As such the label Denisovan is questionable in this case. Moreover, the methods introduced in [1], can predict ethnicity (including archaic humans) with an accuracy of about 80%. As a consequence, it’s at least worth looking into. As noted, all of the code you need to run these experiments are included in [1], save for the additional script attached below. The dataset is also attached below.

Code:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/n34niioi63apczf/Extract_Class_Rows.m?dl=0

Dataset:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/zwt1bcqqmqkleca/mtDNA.zip?dl=0

Discover more from Information Overload

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.