Introduction

When I originally started my work in DNA, I was astonished to find that superficially distinct people (e.g., Nigerians and Norwegians), were 99% matches on their maternal line, as measured by mtDNA. See, A New Model of Computational Genomics [1], generally. That is, 99% of their bases are exactly the same. I mulled through the intuitive suspicions like slavery, but that line of reasoning started to fade quickly, as populations all over the world were again 99% matches, with absolutely no known history to explain it. For example, the people of Thailand and Japan (where there’s no significant history of slavery), are 99% matches with some people in Scandinavia and Africa. Moreover, many people in Scandinavia are 99% matches to a 4,000 year old Ancient Egyptian genome. Slavery simply cannot explain these outcomes, and I am not aware of any history that does. The conclusion I came to is that the world was global a very long time ago, due simply to sailing –

This makes perfect sense, and of course the history could be lost if it’s sufficiently ancient, which it seems to be. Consistent with this hypothesis, there is at least some academic support for a very early migration out of Africa, to Asia, and back to Africa [2], around 70,000 years ago, which could on its own explain these results, without sailing until much later (e.g., allowing for the eventual peopling of Japan and other Pacific islands, which plainly requires sophisticated sailing).

However, I also recently realized that it must be the case that mtDNA carries information about paternal lineage. This follows from the fact that mtDNA alone can be used to predict ethnicity with roughly 80% accuracy, over a dataset of 36 global ethnicities. See Section 5 of [1]. Chance implies an accuracy of . This accuracy is simply too high, unless mtDNA carries information about paternal lineage as well. This is distinct from being able to determine who a given person’s father is, and is instead, information about the paternal line of the person in general, which in turn allows you to predict ethnicity.

We are then confronted with the problem of morphologically distinct people, with the same maternal and paternal lineages. That is, two populations that have very similar distributions of maternal lines, probably have similar distributions of paternal lines as well. My work shows unambiguously that there’s a set of global populations that are 99% matches on the maternal line, which in turn implies that they are probably highly similar on the paternal line as well. However, these populations include Africans, Europeans, and Asians, who are obviously morphologically distinct people. How could this be if they are so genetically similar?

Complexity, Selection, and Competition

I think the answer comes from complexity theory. Specifically, coding for color (e.g., skin or eyes), texture (e.g., hair), and quantity (e.g., size or height), requires very little information compared to coding for structure. Human beings are all structurally the same, and as a consequence, there shouldn’t be much variation in the genetics that codes for overall morphology. Similarly, because color, texture, and quantity are low-information variables, the portion of the genome that codes for these properties will be small relative to the size of the human genome as a whole. In contrast, the brain, nervous system, and sensory organs (e.g., the eye) are incredibly complex systems. As a consequence, they must require significantly more bases to code for than e.g., skin color. Said in simple terms, you can encode variables like size using integers, whereas coding for structure requires information about position and function, which is far more complex, especially for a system as complex as the brain. Keep in mind, the human brain is, as far as we know, the most complex system in the Universe.

You can then ask, why would Nature use efficient codes? And the answer there is that Nature is the most ruthless enforcer of efficiency, and probably why human beings even considered efficient coding in the first instance (i.e., it is the result of competition). Specifically, posit two otherwise identical species A and B. Species A uses a small portion of its genome to code for simple systems in the body, whereas species B uses a large portion of its genome to code for simple systems in the body. The larger the portion of the genome that codes for a given system, the greater the multiplicity of outcomes (i.e., the greater the number of variations that are possible for that system).

This is the case because there are a greater number of sequences that follow from a longer sequence of bases. Note that the number of possible sequences of length is

, and as a consequence, the number of possible sequences grows exponentially as a function sequence length. It follows that species A will reserve a larger portion of its genome for more complex systems, thereby allowing for exponentially greater multiplicity in complex systems. This in turn implies that species A will be more diverse with respect to complex systems like, e.g., the brain, than species B. That is, you have an exponentially larger number of possible brains in species A than you do in species B. For the same reason, species B will allow for greater multiplicity in less complex systems, but this is obviously a waste. Therefore, species A will create more opportunities for selection on the basis of complex systems like the brain, and in the long run, species A will plainly outperform species B.

Genetic Similarity, Morphological Distinction

The logical conclusion is that the reason you have high genetic similarity among morphologically distinct populations is that they have similar brains, sensory organs, nervous systems, and complex systems generally, which should produce similar preferences. The portion of the genome that causes them to appear physically different is likely minuscule when compared to the total genome size. This could explain how e.g., an African person and Asian person, or Northern European person, could all be 99% matches, and as a general matter, share a significant portion of their total genome. More generally, the visible portion of the human body is plainly not the most complex part, nor is it the bulk by mass – the inside is. This implies a question for empirical testing, that is now possible to answer, specifically, whether whole-genomes follow mtDNA. If this is the case, which I suspect it is, given the fact that mtDNA alone can reliably predict ethnicity, at the level of a modern sovereign boundary, then the story of humanity needs to be rewritten, which will in turn change our understanding of not only the present, but history as well. That is, it’s impossible that these genetic connections arose spontaneously, and so there must be a history that brought them to fruition, which implies a very early, and very diverse world.

Historical Implications

As a consequence, our understanding of history is almost certainly wrong, based upon genetics, and also just common sense observation. One glaring example is the Ancient Egyptians, who were visibly Asian people, that seem to have straight hair and somewhat almond eyes, and I suspect based upon genetics and common sense, that they come from Nepal, since they are a 99% match to many modern Nepalese people. And there are other modern day Africans that look very similar, e.g., the Khoisan people, who are also in many cases part of the same global group of people that are mutual 99% matches to each other. If I had to wager, I’d say that we don’t have a good understanding of very early Ancient Egyptian history (i.e., beginning around 10,000 BC), and that the Egyptians initially came from Nepal, and might have been seafaring people for a very long time, prior to forming what we now know as Ancient Egypt. Again, this is consistent with [2], that argues for a migration back to Africa from Asia, around 70,000 years ago.

Whole-Genome Sequencing

Some of this plainly doesn’t come across in traditional genetic research, which focuses on genes, and other signatures in genomes that are statistically common in populations. However, I did reach many of the same conclusions as researchers using traditional techniques (e.g., a migration back to Africa from Asia). Therefore, at the risk of being immodest, because my results are consistent with, but more precise than, traditional genetics, I think it’s fair to conclude the methods introduced in [1] are in general superior. Now, that said, being able to sequence entire genomes is relatively new, and so there is a practical explanation for this, which is that you have limited time and resources, and so you focus on a portion of what is in all honesty a gigantic mathematical object (i.e., the entire human genome). However, my work allows for whole-genome comparison and analysis in polynomial time, and was conceived of after the advent of whole-genome sequencing. As a result, we can now compare entire genomes, even on consumer devices, and therefore, ask questions about whole-genomes.

Moreover, there’s simply no way that traditional genetic research using Haplogroups will produce the kinds of accuracies my work produces. You can see this in the map above, which shows the global distribution of different Haplogroups, which plainly span large geographic areas. In contrast, my software is able to, e.g., distinguish between Norwegians, Swedes, and Finns, again with 80% accuracy, given a dataset that includes 36 global ethnicities. You can see that it is impossible to do this using Haplogroups alone, because it’s sloppy, and breaches national boundaries. If you want to understand exactly why my methods work better, read [1], but for an intuition, you’re starting with a gigantic mathematical object, a genome expressed as a vector of labels, that is potentially millions of characters long. Then, you’re searching for individual, presumably sequential signals that are common to a population. First off, the better signals might not be sequential, and my research suggests instead the best signals are randomly spread over a genome. See Section 7 of [1]. Secondly, even if the best signals are sequential (which is probably not true), there are an enormous and certainly intractable number of sequences to consider, because you have to subdivide populations, because every population is heterogenous (i.e., there are multiple bloodlines in every population). Therefore, you are basically guaranteed to miss some signals that are common to a population, producing the imprecise results above.

Application to Data

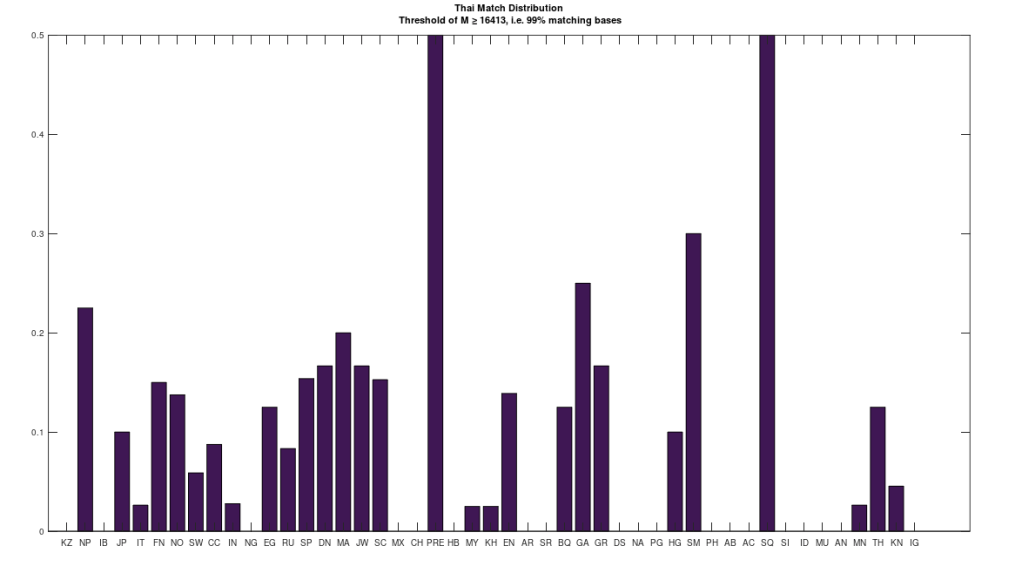

Attached is code that allows you to A/B test populations, and identify where on the genome their bases differ. It also outputs the average number of matching bases. As an example of the theories above, I compared a single Mongolian genome to a single Thai genome, and the number of matching bases is 5,028. Keep in mind that chance implies a match count of one quarter of the genome, which is 4,144 bases. As such, the Mongolian genome and Thai genome have little more than chance in common. I then compared 4 Thai genomes, to the full dataset of ethnicities, and the results are plotted below. The x-axis shows the population acronym (e.g., MN is Mongolian). The full table of acronyms can be found at the end of [1]. If a given Thai genome is a 99% match to e.g., a Norwegian genome, a counter is incremented. The y-axis shows the value of that counter for a given population as a percentage of its maximum. For example, there are 4 Thai genomes, and 20 Norwegian genomes in the attached dataset. As a consequence, the counter for the Norwegian population has a maximum of 80 (i.e., 20 x 4). The chart below shows the value of this percentage for each population on the y-axis, and in the case of the Norwegian population, it is exactly 13.75%. As you can see, there’s a very weak connection between the Thai genomes and the Mongolian genomes, of which there are 19, with a percentage of 2.63%. The plain implication is that despite superficial similarities, Thai people are much closer to Norwegian people, than they are to Mongolians.

In addition, there is a single Saqqaq genome in the dataset, and so 50% of the Thai genomes are a 99% match to that single Saqqaq genome. The Saqqaq were indigenous people that lived in Greenland from around 2,500 BCE to 800 BCE. Greenland is plainly geographically remote from Thailand, and moreover, requires a boat to get to – you simply cannot credibly claim that people can swim through the frozen waters around Greenland, in appreciable numbers. As a consequence, it must be the case that at least some seafaring capabilities existed in indigenous peoples during antiquity, suggesting at least the possibility of sophisticated seafaring people elsewhere. Moreover, the Ancient Egyptians were obviously very sophisticated people, and so they’re a decent candidate for the peopling of the Pacific, which obviously required sophisticated boats, and probably telescopes.

Again, as you can plainly see, many Norwegians are a nearly perfect match to the Thai people. In fact, the maximum match percentage between Norwegians and Thais, is 99.76% of the full genome. This could explain why there are plainly Asian-inspired structures in Norway (and some other parts of Europe) known as Stave Churches, that obviously resemble Thai temples. Note that this is also consistent with the hypothesis that genetically similar people should prefer the same aesthetics, since they have similar brains and sense organs. The conclusion being that despite dissimilar appearances, the Thai and Norwegians are very closely related, whereas the Mongolians and Thai are not closely related. This is contrary to what are plainly racist, unscientific categorizations of people, revealing instead real, and deep genetic connections between superficially dissimilar populations.

The Origins of Diversity and Humanity

I recently noted that it’s basically impossible for random mutations to persist, unless they occur on a mass scale in a given population. I posited that contagious microorganisms are the cause, specifically that microorganisms spread in a given population and cause similar mutations to that population. If those mutations are beneficial, selection will cause them to persist. This is also consistent with a common origin of multiple hominin species out of Africa, since otherwise, there’s really no good explanation for multiple similar hominin species to emerge from the same place. Mathematically, having the same significant random mutation occur twice has a probability of roughly zero, since the probabilities are governed by the Binomial Distribution, which means we should have at most one species of hominin, and there are instead many. In fact, there should have been at most one original human, who would be therefore incapable of reproducing. This idea is obviously wrong. The idea that they should all come from the same place without cause is therefore totally absurd.

If you instead posit the existence of microorganisms somewhere in Africa that cause great apes to mutate into hominins, then you can easily explain the emergence of hominins. This would also explain why e.g., Mongolians, some of whom are closely related to Heidelbergensis, look very similar to other Asians, who are not related at all to Heidelbergensis (e.g., the Thai people). That is, the microorganisms in Asia cause the relevant mutations that change morphology. The work above implies that a very small portion of the genome is responsible for appearance, and it is therefore perfectly plausible that the same mutation occurs to totally distinct people, on a mass scale, causing them to develop a similar appearance, while otherwise having very little in common genetically. However, the portion of the genome separating humanity from the great apes is presumably significant, and as a consequence, it should not occur as often. That is, it should occur more often than chance, because it has a cause (i.e., microorganisms in Africa), but it should occur less often than the mutations that change appearance in Asia, because the portion of the genome involved in appearance is presumably much smaller than the portion involved in transitioning from great ape to hominin.

If less than all of the mutations required to transition from great ape to hominin are effected, then I would wager the organism in question ends up with a genetic disease, and dies off. Similarly, if less than all of the mutations required to transition into an Asian morphology are effected, I would again wager the individual in question ends up with a genetic disease, and dies off. Because there are fewer genes involved in transitioning to an Asian morphology than there are in transitioning from great ape to hominin, the probability of a fatal error should be lower, since the number of mutations is much smaller (i.e., each mutation carries some probability of error, and so the total error is a function of the number of mutations). As a consequence, Asians should look roughly the same, and they do, since it is a “safer” mutation than transitioning from great ape to hominin. Note that I am plainly not considering e.g., Indians in this discussion, and there are of course other populations in Asia that are morphologically distinct, but this is not inconsistent with this hypothesis. In fact, it supports the hypothesis, because it shouldn’t happen all the time, just more often than great apes that transition into hominins, and greater than chance, which is plainly the case, given that a simply enormous number of Asian people have very similar morphology. This, despite the fact that they are plainly not all closely related as a matter of overall genetics.

Here’s the code:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/7477c8hj314bgsw/Genetic_AB_Test.m?dl=0

Here’s the dataset:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/zwt1bcqqmqkleca/mtDNA.zip?dl=0

Any missing code is linked to in my paper, A New Model of Computation Genomics.

Discover more from Information Overload

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.