In my most recent paper, A New Model of Computational Genomics [1], I showed that a genome is more likely to map to its true nearest neighbor, if you consider a random subset of bases, versus a sequential set of bases. Specifically, let be a vector of integers, viewed as the indexes of some genome. Let

be a genome, and let

denote the bases of

, as indexed by

, within

. That is,

is the subset of the full genome

, limited to the consideration of the bases identified in

. We can then run Nearest Neighbor on

, which will return some genome

. If

is the full set of genome indexes, then

will be the true nearest neighbor of

.

The results in Section 7 of [1] show that as you increase the size of , you end up mapping to the true nearest neighbor more often, suggesting that imputation becomes stronger as you increase the number of known bases (i.e., the size of

). This is not surprising, and my real purpose was to prove that statistical imputation (i.e., using random indexes in

) was at least acceptable, compared to sequential imputation (i.e., using sequential indexes in

), which is closer to searching for known genes, and imputing remaining bases. It turns out random bases are actually strictly superior, which you can see below.

It turns out imputation seems to be strictly superior when using random bases, as opposed to sequential bases. Specifically, I did basically the same thing again, except this time I fixed a sequential set of bases of length ,

, with a random starting index, and then also fixed

random bases

. The random starting index for

is to ensure I’m not repeatedly sampling an idiosyncratic portion of the genome. I then counted how many genomes contained the sequence

, and counted how many genomes contained the sequence

. If random bases generate stronger imputation, then fewer genomes should contain the sequence

. That is, if you get better imputation using random bases, then the resultant sequence should be less common, returning a smaller set of genomes that contain the sequence in question. This appears to be the case empirically, as I did this for every genome in the dataset below, which contains

complete mtDNA genomes from the National Institute of Health.

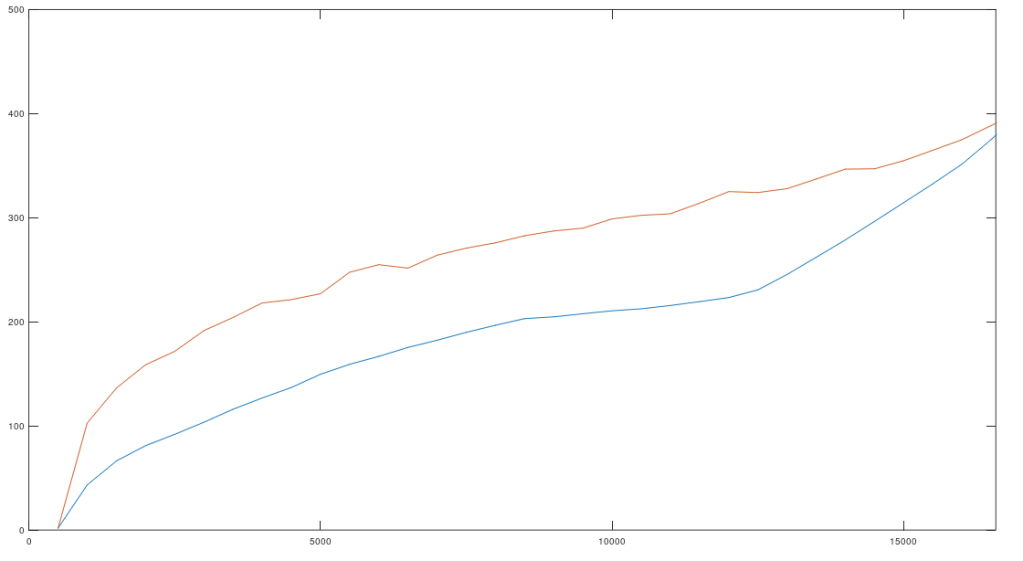

Attached is code that lets you test this for yourself. Below is a plot that shows the percentage of times sequential imputation is superior to random imputation (i.e., the number of success divided by 405), as a function of the size of , which starts out at

bases, increases by

bases per iteration, and peaks at the full genome size of

bases. You’ll note it quickly goes to zero.

This suggests that imputation is local, and that by increasing the distances between the sampled bases, you therefore increase the strength of the overall imputation, since you minimize the intersection of any information generated by nearby bases. The real test is actually counting how many bases are in common outside a given , and testing whether random or sequential is superior, and I’ll do that tomorrow.

https://www.dropbox.com/s/9itnwc1ey92bg4o/Seq_versu_Random_Clusters_CMDNLINE.m?dl=0

https://www.dropbox.com/s/ht5g2rqg090himo/mtDNA.zip?dl=0

Discover more from Information Overload

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.