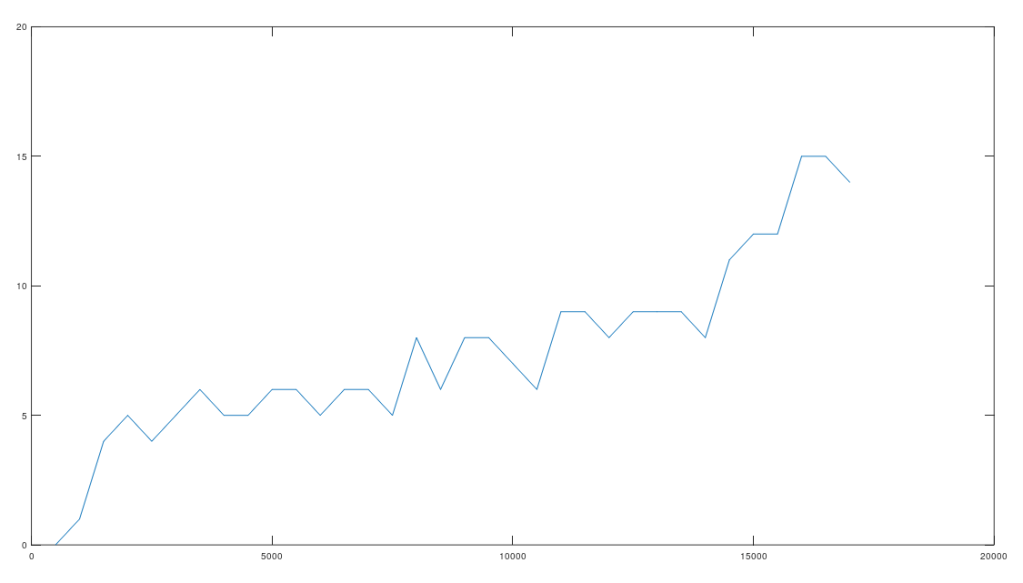

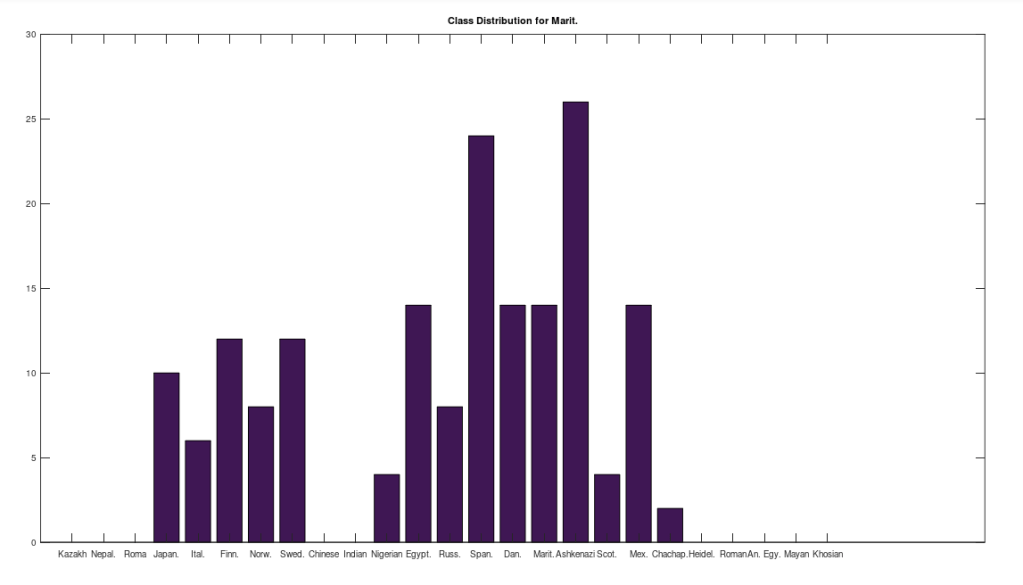

I’ve updated the dataset to account for ethnicity specifically, and so now all genomes have provenance directly tied to e.g., the Chinese, as opposed to simply being sampled in China, by a person that might not be Chinese. This applies to all of the 24 ethnicities, for a total of 341 complete mtDNA genomes. The overall number of rows increased, but some nationalities were reduced in size, because I wasn’t able to confirm ethnicity. The results really didn’t change much at all, so the last few articles I wrote still stand, but I’m still kicking the tires on all of this. That said, this dataset is now thoroughly diligenced, and again includes the raw genomes, together with links to the NIH Database for each genome included in the dataset.

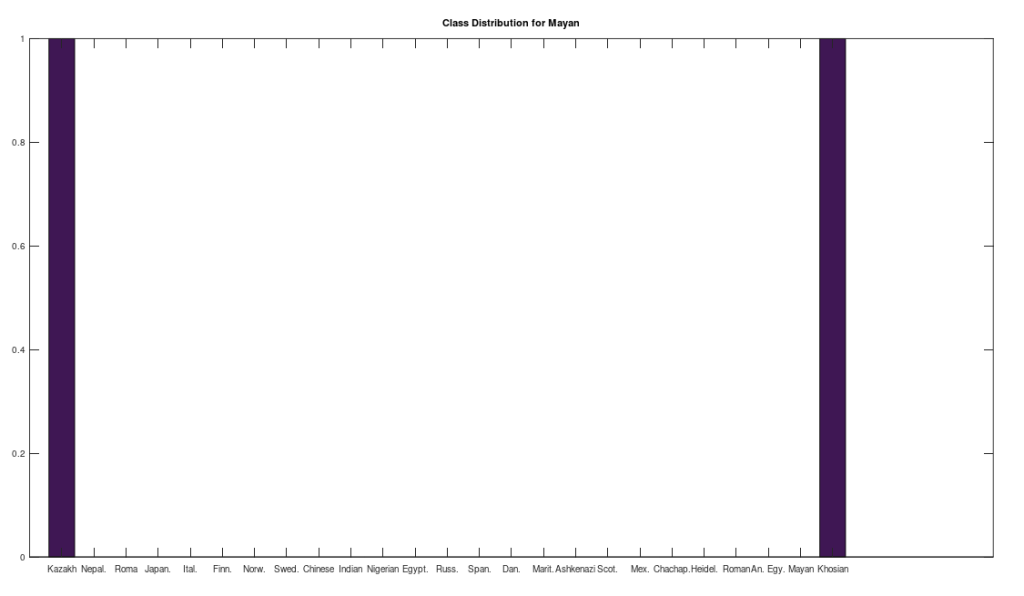

One hypothesis I had that turned true, is that as you increase the number of rows, populations become increasingly concentrated in themselves. As a result, with a huge database like the NIH has, you can probably find a near perfect match for any two populations, but a truly perfect match seems to be limited in number for remote groups. As a consequence, working with a smaller dataset makes sense, if you want to uncover interesting relationships between populations. That said, running a BLAST search is a good sanity check for any hypothesis.

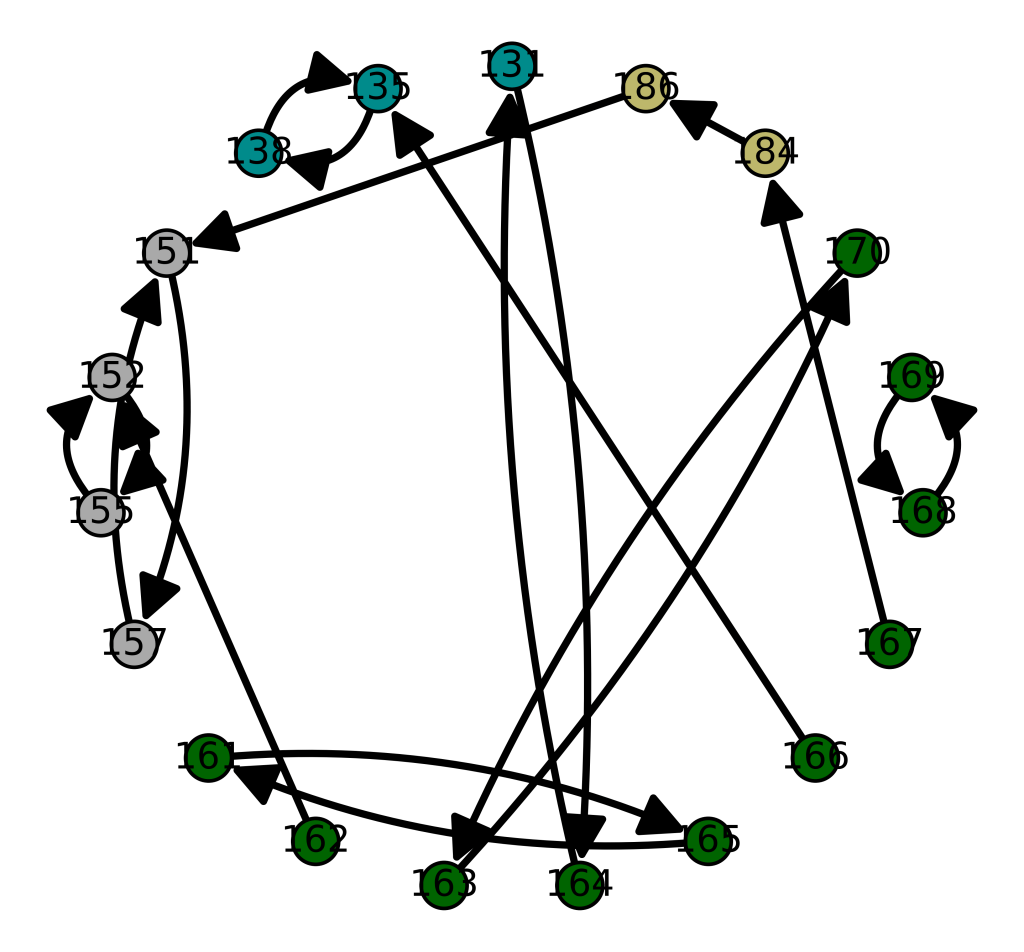

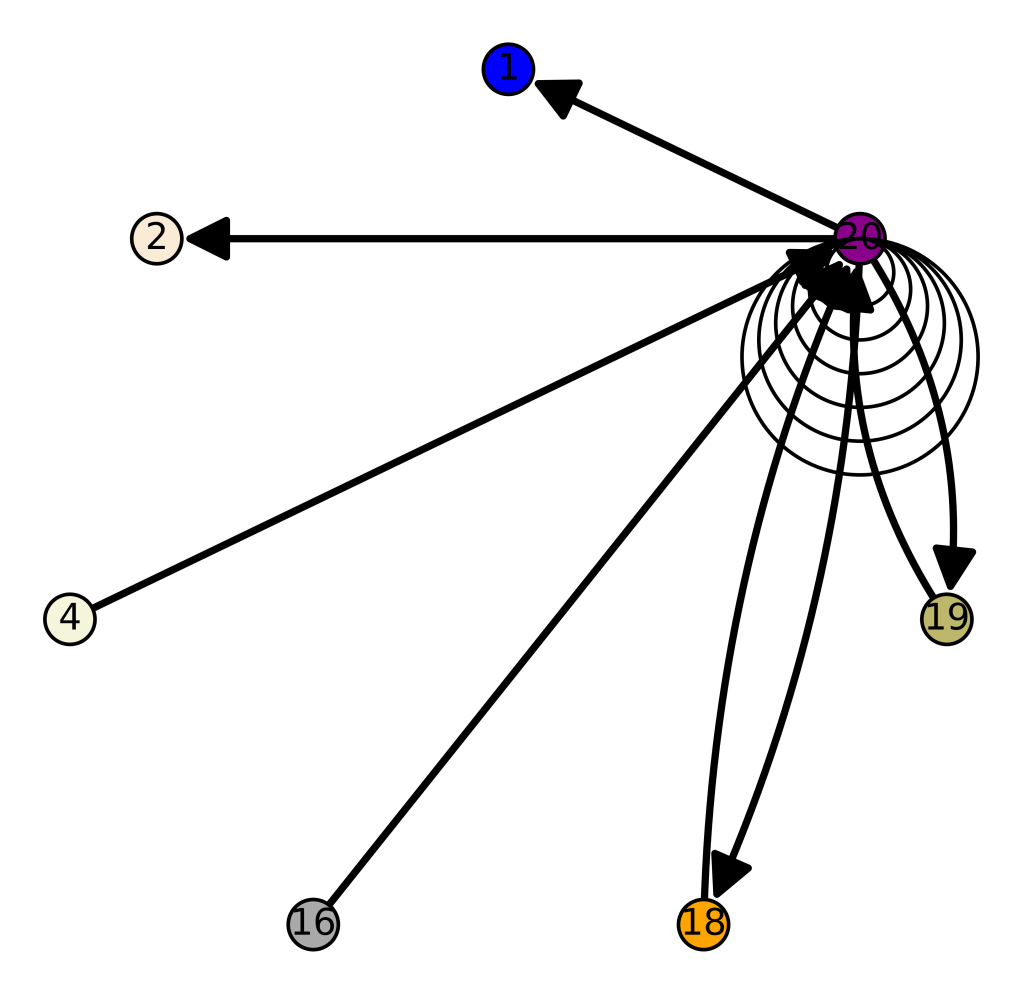

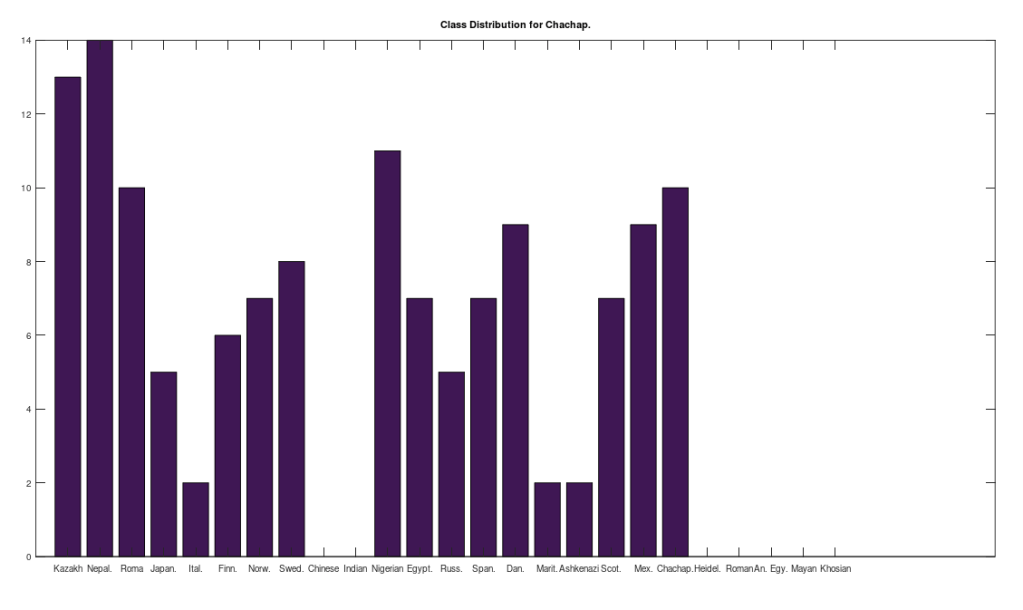

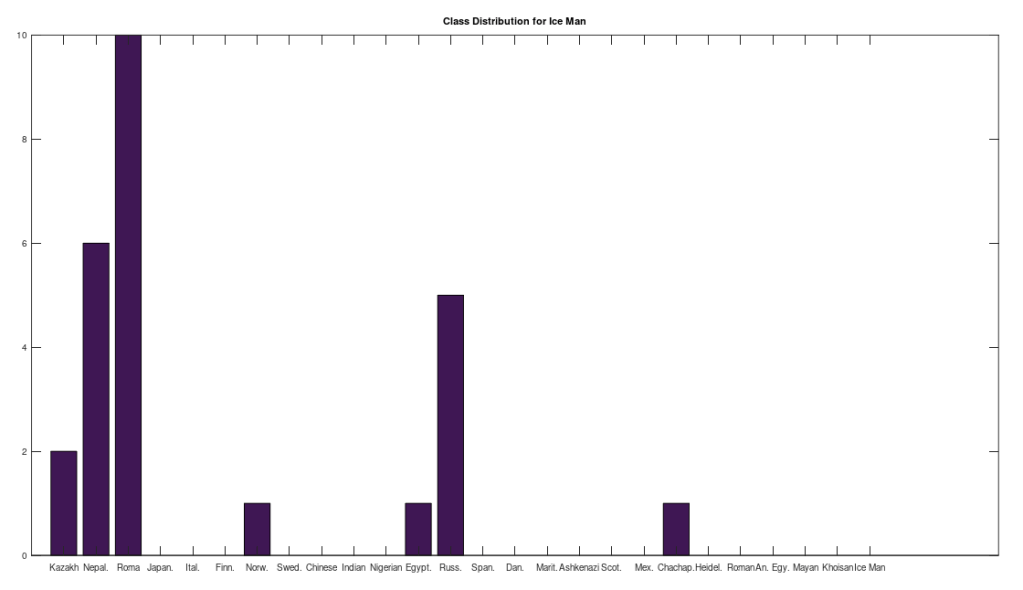

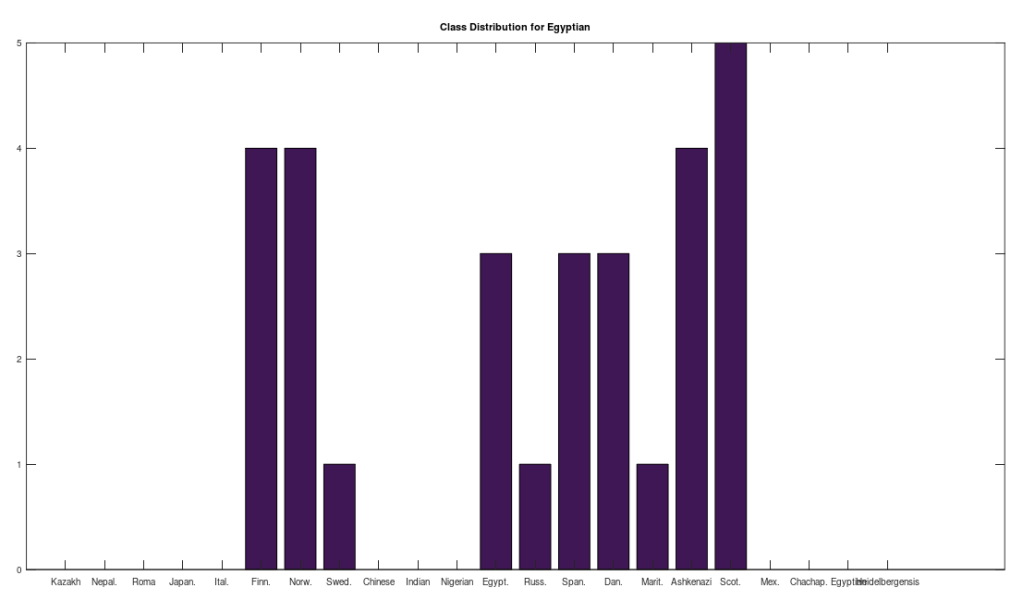

One shocker, I found a 4,000 year old, Pre-Roman Egyptian complete mtDNA genome, and its closest matches in the dataset below are a Norwegian and a Dane (graph above). I just proofed it using BLAST, and it seems like it’s legit, as a near perfect match comes up with an ethnic Norwegian. This is consistent with the last few posts I’ve shared, showing a strong genetic connection between the Nordic people (if you include the Scotts) and a global population that reaches all the way from South America to Polynesia, that seems to predate the Vikings. I would wager again, the world was globalized, a really long time ago, and it could have been the result of sailboats and possibly early telescopes, or something close that would allow you to spot land over huge distances, rather than meander at sea and therefore almost certainly die in places like Polynesia, where the distances between islands are way beyond human vision.

I tested it even further, and bizarrely, the Scotts yet again, show up as the dominant group for the 4,000 year old ancient Egyptian genome. Note again, this is a dataset of complete genomes, including two African countries (Nigeria and Egypt itself), and the Scotts are the dominant group when you set the minimum matching base count to 99.7% of the genome. This is not, to my knowledge, consistent with known history, and suggests yet again, the world was significantly globalized, a very long time ago. Interpreted literally, this means 5 out of the 20 Scottish genomes in the dataset were a 99.7% match to a 4,000 year old Egyptian genome.

The bottom line conclusion is that many Scottish people are plainly of Ancient Egyptian heritage on their maternal line. You can fuss that the number of genomes per population is not uniform, but this doesn’t change the percentage of Scotts that match, which is plainly high. Moreover, there are 20 modern Egyptian genomes and 20 Scottish genomes, and the Scotts plainly fit better. Further, there are 19, 20, and 18 Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish genomes, respectively, and the Swedes are plainly not as closely related to the Ancient Egyptian genome, suggesting that it’s not a simple matter of geography. Finally, that any of the Northern Europeans are this closely related is simply baffling, since, e.g., why aren’t the Nigerians and Italians related? They’re geographically proximate, with some kind of sensible historical connection. This is irrefutable, and simply not consistent with known history.

Rather than give the Scotts any special credit, I think the takeaway is instead that the world was already diverse a very long time ago, and this is consistent with the distribution of aesthetics in the world before Christ, in particular in Ancient Egypt, which plainly depicts racially diverse people, though this is not true during Cleopatra’s reign, when people seemed more or less Mediterranean. On the left is the Berlin Green Head, in the center is Menkaure and Queen Khamerernebty II, and on the right is Nefertiti, images courtesy of Wikipedia, MFA Boston, and Wikipedia, respectively.

You’ll note that none of these people look Mediterranean, and in my opinion, they look to be of mixed heritage, demonstrating African, Asian, and European features. They could instead be so ancient that they are like the Khoisan, who have similar mixed features, but that is apparently not supported by the dataset, suggesting that they really were multi-racial people. When you look at the level of skill in their work, I have no trouble believing it, as they were plainly an advanced people, and it requires advanced people to produce multi-racial people, in particular, royalty. I doubt there are many living artists capable of producing works on this level, and regrettably, many people still struggle with simply getting along with superficially different people. The cruel justice of this work is that it’s all nonsense, and our histories have apparently been mixed up for quite a long time.

Here’s the dataset: