In a previous note, I demonstrated that randomly selected bases are better at predicting the nearest neighbor of a given genome, than a contiguous sequence containing the same number of bases. That is, if you want to predict the nearest neighbor of a genome over a dataset, and you can use only out of a total of

bases, you will produce better results if you randomly select the indexes of the bases, rather than use a contiguous sequence of bases of length

. This is counterintuitive, but it makes sense if the bases are not truly independent of one another. This is probably mechanically true, since protein production occurs in consecutive sequences of three bases. As a consequence, it makes sense to spread the selection of the

bases randomly over the entire length of the genome, thereby minimizing the intersection of the information provided by the bases, and therefore maximizing the union of the information provided by the bases. I also showed in the previous note that whether you use sequential contiguous bases, or randomly selected bases, the nearest neighbor of a given genome becomes more likely to be predicted as a function of the number of matching bases

.

There is still however the more general question of whether, given some genome , and set of base indexes

, knowledge of the bases

implies knowledge about the genome

generally, beyond the bases in

. If this is true, and genome

is the true nearest neighbor of

, then it should be the case that genomes

and

have matching bases outside of the base indexes in

. That is, if the bases in

fix some other bases outside the indexes in

, then it should be the case that

and

have other bases in common in those regions (i.e., the base indexes not included in

). We can of course test this experimentally, and the attached code does so over a dataset of 206 complete human mtDNA genomes. In fact, the condition in the attached is much more stringent, and instead requires that the nearest neighbor of

, genome

(i.e., the nearest neighbor of

when consideration is limited to indexes

) maximizes the number of matching bases outside

. That is, if there is any genome other than

that has more bases in common with

beyond

, then genome

is disregarded. If instead the condition is satisfied, a counter is incremented. This test is done for increasing values of

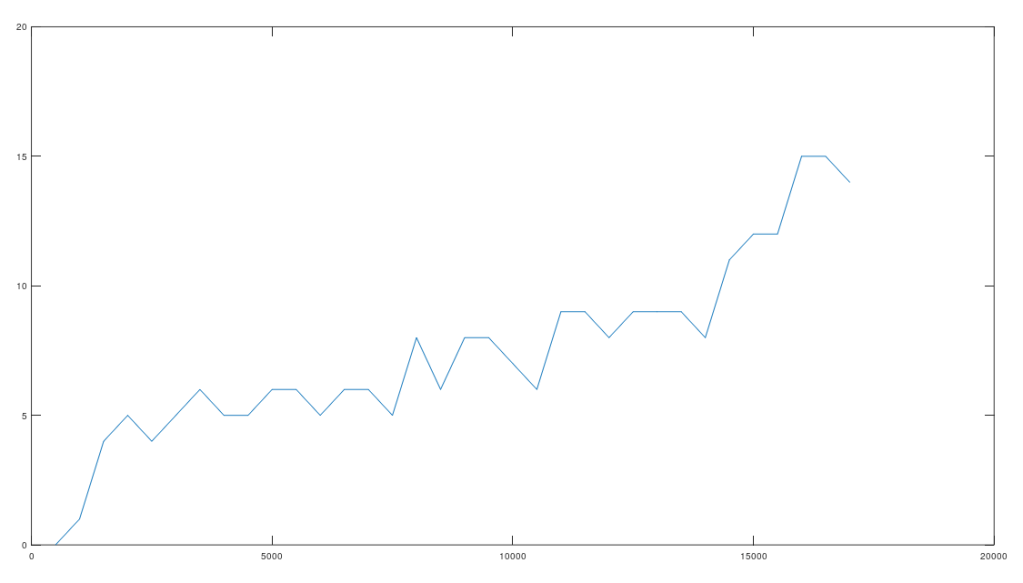

, where

is the size of

, plotted below, where the horizontal axis shows the value of

, and the vertical axis shows the number of rows that satisfy the condition. Note again that

is randomly selected, and not contiguous.

Note the while the number of rows that satisfy the test condition might seem small, the probabilities are given by the Binomial Distribution, where the number of trials is equal to the number of genomes in the dataset (206), the number of successful outcomes is given by the values along the y-axis, and the probability of success is . All of this can be understood by noting that if this were the result of chance, then once the nearest neighbor of a given row is fixed, the row that maximizes the match count beyond a given

can be selected in

ways. Note that a single successful outcome has a probability of about

, whereas

successful outcomes has a probability around

. As a consequence, it is not credible to claim that the graph above is the result of chance. Instead, it is more sensible to assume that imputation is a phenomenon justified beyond the existence of genes and haplogroups, and is instead a fundamental statistical property of genomes.

Finally, note that imputation is, mathematically, an abstract form of symmetry, where the part implies the whole, just as a set of points is projected over an axis of symmetry in the plane. The difference in this case is that DNA could be Kolmogorov random, and so the only inference available would be statistical, rather than structural. Specifically, that because is the nearest neighbor of

, they will with some probability have some number of bases in common outside

.

Below is the code for this analysis. The dataset and the underlying function code can be found in the previous post:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/58b923h1adq7z5v/Abstract%20Symmetry%20CMDNLINE.m?dl=0

Discover more from Information Overload

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.