In a previous note, I pointed out that using the typical NIH mtDNA alignment, homo sapiens generally have the same 15 opening bases in common, despite the fact that mtDNA is circular, which are as follows:

GATCACAGGTCTATC

Note that this is too long to be credibly attributed to chance. I am assuming that the NIH alignment is the result of analysis that maximizes a metric related to the number of matching bases across their database, for a given species, that is then shifted to create exactly this common opening sequence (rather than e.g., beginning with a highly variable portion of the genome). Note that because mtDNA is circular, the exact order does not matter, provided the shift is consistent across the database, and so presenting the data in this manner makes perfect sense. I also pointed out that this creates two signature profiles when comparing genomes, one for two genomes that are a match (i.e., the two genomes have a high percentage of matching bases), and one for two genomes that are not a match (i.e., they have a low percentage of matching bases).

The average percentage of matching bases (y-axis) as a function of base index (x-axis).

Specifically, if you count the average number of matching bases from index 1 to index K, using the NIH alignment, and increase K, you find that if two genomes in fact have a high number of matching bases, the curve plainly converges to around 99% to 100%. In contrast, two genomes that don’t match instead diverge from a high matching percentage to around 25% (i.e., chance). This produces curves that are useful for Machine Learning, since it implies an unsupervised clustering algorithm, where two genomes are clustered together if they produce an upward sloping curve, and are otherwise, not clustered together. Note that you don’t have to test the overall matching base percentage using this method, and it is therefore totally unsupervised.

The plot above shows 10 complete Nigerian mtDNA genomes compared to a single Japanese genome. The x-axis is the genome index, and the y-axis is the percentage of matching bases, from index 1 up to the x-value. Most of the Nigerian genomes plainly do not match, and so they diverge, whereas some plainly do (converging at the top). There’s also an outlier in the middle, which you can consider as a third class that is a partial match, or simply disregard, as the bottom line is, this produces a useful unsupervised clustering algorithm that could be used to group mtDNA genomes beyond obvious geographies or other known connections.

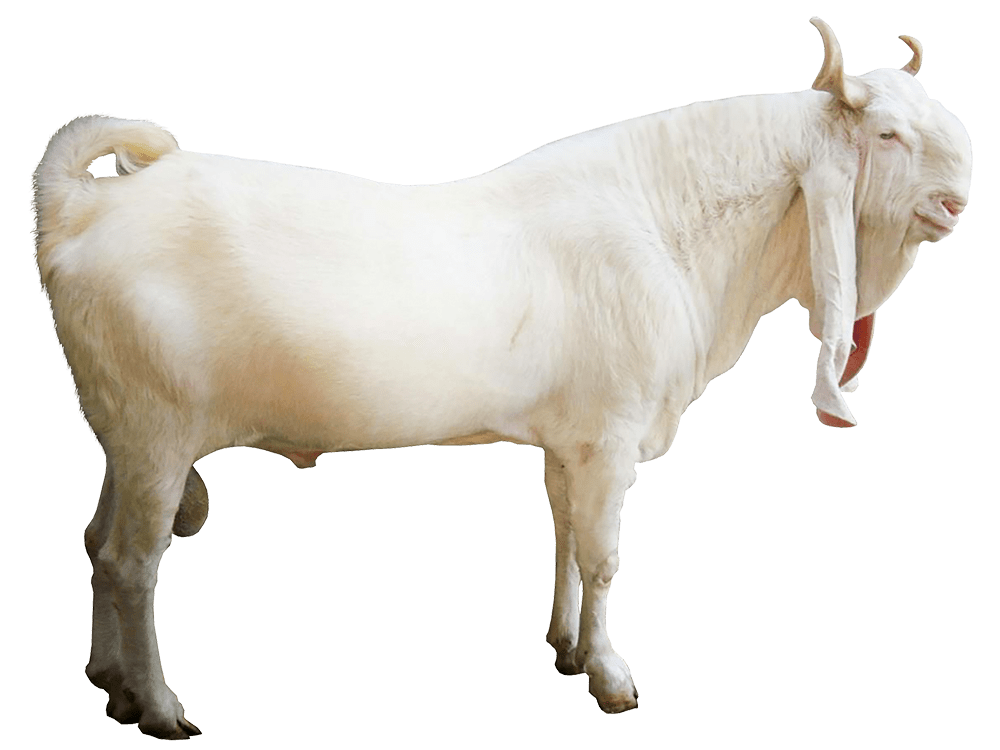

I’ve expanded this inquiry into four other species formally, and several others anecdotally, and it seems the same is true of those species. Moreover, differences in the otherwise common opening mtDNA sequences are plainly associated with significant morphological distinctions. For example, the Gorilla and Chimp genomes in the dataset have perfectly consistent opening sequences of length 193 and 19, respectively. In contrast, the Goat and Carp genomes have consistent opening sequences of length 1 and 2, respectively, though closer examination shows that subsets of those genome groups have substantial overlap in their opening sequences. One sensible interpretation, is that a long, consistent opening sequence is unique to Humans, Chimps, and Gorillas. Another interpretation is that Humans, Chimps, and Gorillas, are within their own species morphologically roughly homogenous, whereas the same is plainly not true of Carp and Goats, both of which contain a wide variety of what could be fairly described as subspecies or breeds. The images below shows plain morphological differences between the Black Bengal Goat, and the Jamnapari Goat, including different coloring, hair lengths, horn shape, and face shape.

Bengal Black Goat (left) and a Jamnapari Goat (right).

It follows then that a morphologically consistent species such as the Emperor Penguin should produce alignments with a consistent opening sequence. Running a BLAST search for this specimen genome produces exactly that result, with a consistent opening sequence for the results returned. Simply look through the Alignment page, and you’ll note that there are no adjustments at all (i.e., the Subject index equals the Query index), and that the bases are consistent over the opening line of 60 bases. This is not a comprehensive study, but given that these are complete genomes, from a wide variety of human populations, and a reasonable number of non-human species, it is a credible hypothesis. Specifically, that variance in the opening sequence of an idealized alignment for a population of mtDNA genomes is consistent with significant morphological diversity. Further, it is also consistent with the hypothesis that the populations in scope should be subdivided until they produce a single opening sequence of appreciable length (i.e., beyond chance).

Emperor Penguins.

Note again that because mtDNA is circular, changes to the specific indexes are irrelevant, provided they are consistent, allowing us to compare what are then the opening sequences (i.e., shifting until we find the most consistent portion of the data across all genomes). In contrast, changes to the alignment that imply insertions or deletions are in fact significant. Moreover, in other contexts beyond mtDNA, insertions and deletions are plainly associated with morphological distinctions, specifically Down Syndrome and Williams Syndrome, as both produce distinct morphological changes to human beings, that are generally consistent in people with those disorders. Down Syndrome is due to a massive insertion, specifically an additional chromosome, and Williams Syndrome is due to specific deletions on Chromosome 7.

The net conclusion is that insertions and deletions in mtDNA seem to be associated with morphological variance, and because human beings are so superficially diverse, yet contain exactly the same opening sequence, it follows that the amount of variance required to generate significant differences in alignment should be quite drastic. There are however some examples within human populations that imply insertions and deletions, when compared to the majority of samples. Specifically, as I previously noted, some Japanese people have minor insertions and deletions to this opening sequence. More significantly, Iberian Roma are a near-perfect match with Homo Heidelbergensis (i.e., around 98% of bases matching), without any changes to the alignment of their mtDNA, using the standard NIH alignment. The code attached below will allow you to make this base-by-base comparison, without adjustment to alignment. In contrast, most other genomes in the dataset produce a number of matching bases around chance (i.e., around 28%) when compared to Heidelbergensis. This is astonishing, and running a BLAST search comparing e.g., an Italian genome to Heidelbergensis, the alignment is adjusted significantly, effectively deleting about 300 bases, producing again a match percentage of 97%. However, this completely ignores the observation that insertions and deletions are associated with drastic differences in morphologies, and behaviors. This at least suggests the possibility that populations that are close to Heidelbergensis, without adjusting alignment, have more in common in terms of appearance and behavior with Heidelbergensis, than those that don’t. At a minimum, it suggests that they have a closer genetic relationship to Heidelbergensis than the general population, that does not require adjustments to alignment to account for insertions and deletions unique to Heidelbergensis and some other apparently related populations. Note that both Iberian Roma and Heidelbergensis contain the exact same opening sequence above that is common to the vast majority of homo sapiens, suggesting that we are the same species, and simply variants of that species. The same is true of Denisovans and Neanderthals.

Below is some code that will allow you probe the dataset, together with the dataset itself, that now consists of 180 complete mtDNA human genomes from 18 geographic populations, 1 complete Heidelbergensis genome, and 20 complete non-human genomes from 4 different species, specifically, Gorilla, Chimpanzee, Goat, and Carp.

https://www.dropbox.com/s/i0ly3hlg0cvzet6/mtDNA_Prefix_CMDNLINE.m?dl=0

https://www.dropbox.com/s/br0krmjjkncms2t/Compare_to_H_Heidel_CMNDLINE.m?dl=0

https://www.dropbox.com/s/casfm3i07v0vefl/Count_Matching_Bases.m?dl=0

https://www.dropbox.com/s/lxq8gfb4h0p8edw/mtDNA.zip?dl=0

Discover more from Information Overload

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.