I’m continuing to work on the applications of Machine Learning to Genomics, and my work so far suggests that genetic sequences are locally consistent, in that the Nearest Neighbor method generally produces good accuracy. More importantly, the Nearest Neighbor of a given sequence seems to be determined by only a fraction of the total sequence. Specifically, if we sample a random subset of the bases, and increase the size of that subset, sequences quickly converge to their true Nearest Neighbor. That is, even if we use only a fraction of the bases, the Nearest Neighbor method returns the true Nearest Neighbor that would be found if we used all of the bases. This is surprising, and is consistent with the hypothesis that bases are not truly random. Specifically, this is consistent with the hypothesis that a small number of bases, determines some larger number of bases. The attached code randomly selects an increasing number of bases, and applies the Nearest Neighbor method. Because the base indexes are randomly selected, it suggests that every subset of a sequence partially determines some larger sequence.

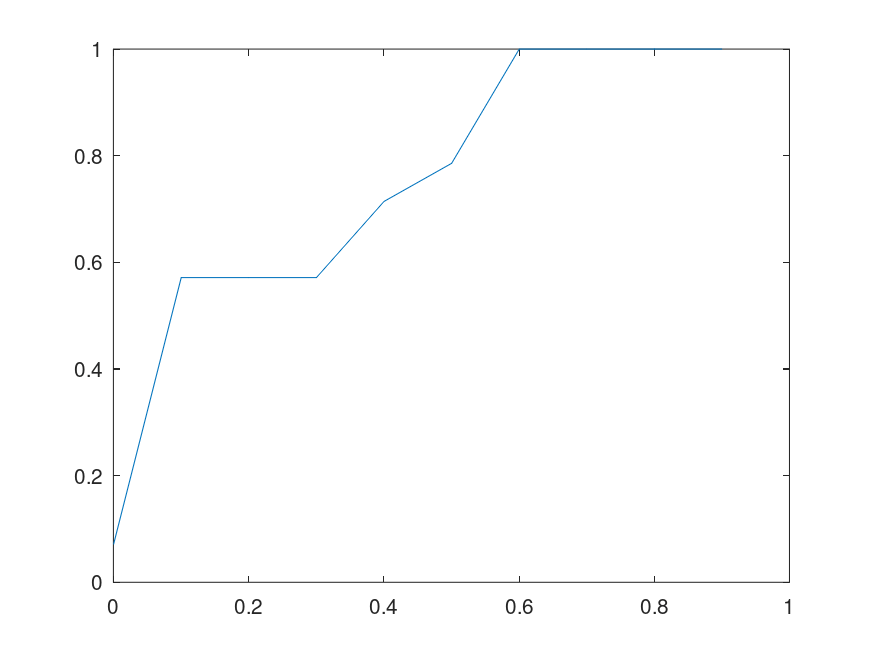

If this is true, then genetic sequences are not truly random. If they are not truly random, how do we explain the diversity of life, even given the amount of time in play? Note that this would not preclude randomized mutations to individual bases, but it does suggest that a sizable number of randomized mutations will cause an even larger sequence to mutate. Below is a plot of the percentage of sequences that converge to their true Nearest Neighbor, given of the bases in the full sequence (i.e., the horizontal axis plots the percentage of bases fed to the Nearest Neighbor algorithm). The plot on the left uses the genome of the Influenza A virus, and the plot on the right uses the genome of the Rota virus. Both are assembled using data from the National Institute of Health.

This brings genetic sequences closer to true computer programs, because in this view, not all sequences “compile”, and as a consequence, if two sequences match on some sufficiently large but sufficiently incomplete number of bases, then they should match on an even larger subset of their bases, since the matching subset fixes some larger subset of the bases. This would allow for partial genetic sequences to be compared to datasets of complete genetic sequences, potentially filling in missing bases. If this is true, it also casts doubt on the claim that the diversity of life is the product of random and gradual changes, since the number of possible base-pairs is simply astronomical, and if most of the possible sequences don’t code for life, as a result of possibility being restricted by selection, you’ll never get to life in any sensible amount of time, because all the sequences that contain prohibited combinations will be duds, and not persist, thereby cutting short that path through the space of possible sequences. In other words, this would require luck, to simply land at the correct mutations, rather than gradually arriving at the correct mutations in sequence.

We can resolve this by allowing for both small-scale mutations, and large-scale mutations, which could lead to drastic changes in measurable traits. In other words, this doesn’t preclude evolution, it simply requires evolution to be extremely subtle (i.e., some small number of bases mutate), or drastic (i.e., some large number of bases all change together). In summary, if this is true, then mutations are either small in number, or sufficiently large in number, causing an even larger sequence to change, generating either duds, or traits that are permitted. Natural Selection would then operate on the traits that are permitted, allowing the environment to determine what traits persist in the long run.

Discover more from Information Overload

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.